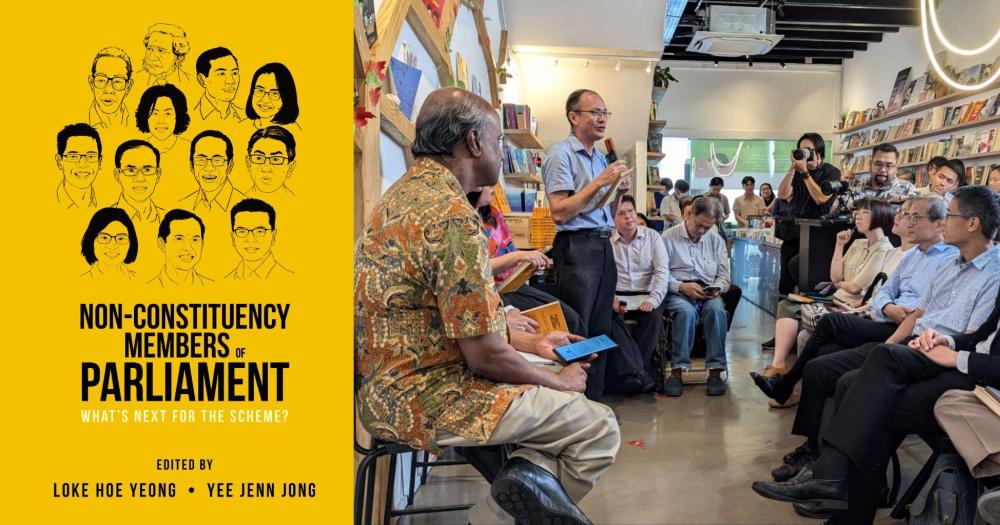

The PAP introduced the NCMP scheme in 1984 to ensure Opposition presence. How well has it worked?

Soft truths to keep Singapore from stalling.

Non-Constituency Members of Parliament: What’s next for the scheme? is a book about the Non-Constituency Member of Parliament scheme and its evolution since its inception in Singapore politics in 1984.

Edited by Loke Hoe Yeong and Yee Jen Jong, the book brings together insights from several analysts and politicians about the impact of the NCMP scheme on Singapore’s politics since it was introduced.

Here, we reproduce excerpts written by Yee and the fifth Attorney-General of Singapore, Walter Woon, about the rationale behind the introduction of the NCMP scheme and how it has been amended to provide for a greater Opposition presence in Parliament, and whether this factored into the choices of voters.

Non-Constituency Members of Parliament: What’s next for the scheme? is published by World Scientific and can be purchased here.

By Walter Woon

Provision for NCMPs was made in the Constitution of the Republic of Singapore (Amendment) Act 1984.

At the second reading of the amendment bill, then Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew explained the rationale for the scheme:

"The main objective of the proposed legislation is to ensure that there will be in Parliament a minimum number of Opposition representatives.

If in the general elections less than the minimum number is returned, then Opposition party candidates who poll the highest percentage of votes will be declared returned as non-constituency Members to bring the number up to the prescribed minimum.

It is proposed that this minimum be three non-constituency Members. However, the number can later be increased by Parliament to six. The effect of the legislation, therefore, is that it as has happened in the past four general elections, the PAP wins all seats, there will still be in this Chamber at least three Opposition Members."

The bill was passed by 66 votes to one, with one abstention. Thus, the main reasons for introduction of NCMPs were:

- PAP Ministers and MPs needed practical experience of dealing with an opposition;

- The voters needed to be educated about what an opposition in Parliament would be capable of doing;

- Opposition MPs would give vent to any allegations of misfeasance, corruption or nepotism;

- Younger voters should feel some pain when voting for incompetent opposition members.

Of the four reasons that Mr Lee propounded, the first clearly is obsolete. Opposition members have been elected regularly, the latest batch being the largest since Independence. There is now an official Leader of the Opposition.

The second reason was based on his experience of the destructive and obstructive Communist-leaning opposition of the turbulent years before Independence.

However, even in 1984 Lee underestimated the sophistication of younger voters. He did not appear to realise that those younger voters who had grown up in post-Independence Singapore pledged every school day to build a democratic society based on justice and equality.

It should not have surprised him that some people actually came to believe in this.

The fourth reason is an example of the attitude that made some people mad enough to vote for the opposing candidates, just to spite the PAP. One trusts that such attitudes have been banished for good from the minds of the ruling party.

This leaves just the third reason, to "give vent to any allegation of misfeasance or corruption or nepotism."

This justification remains as true today as it was in 1984. Singaporeans are sophisticated enough to know that unchecked power tends to lead to abuse. For this reason alone, the presence of MPs from opposition parties is essential for good governance.

The lone dissenting voice speaking against the introduction of NCMPs in 1984 was Workers’ Party (WP) MP Jeyaretnam. His view of the proposal was as follows:

"I say, Mr Speaker, Sir, that this Bill is a fraud on the electorate. If the Prime Minister is genuine in his desire to see Opposition Members in Parliament and therefore bring about parliamentary democracy in Singapore, then may I tell him that there are other ways of doing this, far better ways than this sham Bill… not toothless Opposition Members, as you would have them, but genuine Opposition Members chosen by the electorate, who will come here to serve the citizens of Singapore."

In the four decades since the introduction of NCMPs they have become a fixture in Parliament, albeit one that will self-destruct if ever there are sufficient directly elected opposition MPs.

The current version of the Constitution provides for 12 non-constituency members to "ensure the representation in Parliament of a minimum number of Members from a political party or parties not forming the Government."

This has been the position since 2016, when the Constitution was amended to increase the number of NCMPs and remove the restrictions on their voting rights.

Thus, Jeyaretnam’s categorisation of NCMPs as “toothless” is no longer the case, if it ever was. An effective slate of NCMPs can have influence far beyond their meagre numbers, especially in these days of social media.

By Yee Jenn Jong

1984 GE

The 1984 General Election was the first time the NCMP scheme came into play and understandably, it was used extensively by the PAP during campaigning to assure voters that they could safely vote for the PAP and yet have opposition representatives in Parliament.

That did not seem to work given the massive 12.9 per cent national swing against the ruling party.

Then Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew had expressed surprise that the swing against the PAP was bigger than he had expected.

It was the first time since Independence that the PAP received less than 70 per cent of the overall votes.

In the next general election on 3 September 1988, the PAP vote share declined slightly to 63.1 per cent.

Two NCMP positions were offered to Francis Seow and Dr Lee Siew Choh of the WP for garnering 49.1 per cent votes share in Eunos GRC.

Just before the election, Seow was detained without trial under the Internal Security Act. He then left Singapore after release to seek medical treatment and never returned to face trial for alleged tax evasion. Seow was disqualified from taking up the position.

Lee became Singapore’s first NCMP, making his return to Parliament 25 years after being legislator for the PAP and then for Barisan Sosialis.

Then it became nine

In July 2010, the Constitution was amended to provide automatically for nine opposition members in Parliament.

According to the government, the key reasons for the changes were:

- To cater to citizens who have become better educated and informed, with a growing desire to see greater diversity of views on issues discussed and debated in Parliament;

- To acknowledge that the four NCMPs Parliament had since the start of the scheme had fulfilled the government’s original intent for it, and it was time to increase the allocation to be the same as that for NMPs (nine).

The amendment to the Constitution was opposed by the WP (represented by Low; Lim spoke extensively during the debate to oppose but was not able to vote as an NCMP) and the Singapore Democratic Alliance (represented by Chiam).

The 2011 General Election that followed was a landmark one.

The ‘GRC fortress’ of the PAP which came into effect in the 1988 General Election, had finally been breached by the WP in Aljunied GRC.

Six opposition candidates from the WP were elected — five from Aljunied GRC and one from Hougang SMC.

After sharply reversing their decline in vote share in the 1997 General Election, the PAP also suffered a significant drop of 6.46 per cent in popular votes to 60.14 per cent, its lowest since Independence.

With six elected opposition MPs, the three NCMP positions went to Lina Chiam of the SPP and Gerald Giam and Yee Jenn Jong of the WP.

NCMP scheme appeared to be negligible among voters’ considerations

Did the increase in the number of NCMP seats have any effect on the voting?

Looking at the result which saw an erosion in the ruling party’s vote share and the highest number of elected seats for the opposition since Independence, it did not seem to benefit the PAP.

Other factors appeared to have negated the benefit to the ruling party of assuring the voters that they could still have the PAP government and opposition voices in Parliament.

The reverse fear of a total opposition wipeout and the potential loss of a respected opposition parliamentarian like Low seemed to weigh heavily on voters’ minds, particularly amongst Aljunied and Hougang voters.

Threats made against voters by the PAP in hotly contested Aljunied also appeared to have backfired.

As with all general elections before this, the issue of NCMPs continued to be a topic used by both the PAP and the opposition candidates in 2011.

During a television forum, Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong refuted claims that NCMPs were not a “real opposition” as they could speak in Parliament and that the scheme acknowledged both "the desire among Singaporeans for alternative voices and the need for an opposition to represent the diverse views in society".

As an active campaigner in the 2011 General Election and an NCMP as a result of that general election, this author (Yee) thinks that the NCMP scheme had a minimal effect on how voters cast their vote in that landmark poll.

Even with the increase in the number of NCMP seats, the excitement of the scheme only happened after the polling results where all eyes would be on whether opposition candidates would be NCMPs and if so, who would be qualified to be NCMPs by being the ‘best losers’.

This author did not come across any voter asking him about this matter during campaigning.

The interactions appeared more on whether his party or himself would be the appropriate choice to represent them as a fully elected representative.

The author acknowledges that the NCMP scheme could have an effect of encouraging higher

participation in a general election by opposition candidates as there was an increased chance for opposition candidates to be in Parliament to have the platform to prove themselves.

This was however the last thing on my mind as I was focused on campaigning to be a fully elected legislator.

2015 GE

The arrangement for a maximum of nine NCMPs continued in the 2015 General Election.

The WP retained Hougang SMC and just held on to the Aljunied GRC seats by less than 1 per cent of the popular vote.

It was a big win for the ruling PAP. Singapore’s highly respected founding father, Lee Kuan Yew had passed away in February of that year and it was also the 50th anniversary of Singapore’s Independence.

With huge publicity from the 50th anniversary and the immense gratitude that Singaporeans had for the late Lee, there was a massive 9.72 per cent vote swing back to the PAP.

The Punggol East SMC, which was won by Lee Li Lian of the WP in the 2013 by-election was regained by the PAP.

The resulting three NCMP seats were all offered to the WP — to Lee Li Lian who contested in Punggol East SMC, Dennis Tan who stood in Fengshan SMC and Leon Perera who was part of the opposition party’s East Coast GRC team.

Lee Li Lian rejected the seat and it was eventually filled by Associate Professor Daniel Goh of the East Coast GRC team.

And now there are 12

A year after GE2015, the ruling party proposed to increase the maximum number of NCMPs to 12 and also to give NCMPs the same voting and speaking rights in Parliament as the elected MPs.

The increase to 12 was formalised in 2019, a year before the 2020 General Election.

The PAP’s main arguments for the increase were:

- To recognise that NCMPs have as much of a mandate from voters as constituency MPs;

- To cater for the electorate’s desire for an opposition voice in Parliament in view that the opposition had garnered at least 30 per cent support in past elections; hence an increase to 12 opposition MPs inclusive of NCMPs in a 100-member House was reasonable.

The changes were opposed by the WP, then the only opposition party in Parliament. The WP repeated its call for greater changes to the political system for a more level playing field.

Dennis Tan, then an NCMP, in a Mandarin speech during the debate on the Constitution Amendment on NCMPs, Nov. 8, 2016, said:

"The PAP is hoping that a system with more NCMPs will distract the electorate from the need to vote in elected MPs from alternative parties.

This is to entrench the Parliament supermajority of the PAP. We need more than just NCMPs to check the Government. We need a good political system whereby a check and balance mechanism on the Government can be implemented through a fair and competitive election process."

The 2020 General Election was also a 'Covid-19' General Election, with campaigning severely restricted due to the ongoing pandemic and the absence of any public rallies.

It was a general election that should have benefitted the ruling party given the massive support package of nearly S$100 billion to save jobs.

With the general fear amongst the electorate at a time of global crisis, the PAP touted its steady records for steering Singapore out of previous crises.

There was also the increased guarantee now of 12 opposition representatives through the NCMP scheme.

Given the increase in the number of available NCMP positions, it was not surprising that the PAP brought the issue up several times during campaigning.

The opposition, notably the WP which had the highest share of the NCMP positions historically and all of the NCMPs in the 2015–2020 Parliament term, also argued fervently why the scheme did not provide for the real competition and opposition that Singapore needed.

The general election also saw a new party, the Progress Singapore Party (PSP) founded by former seven-time PAP MP Dr Tan Cheng Bock who also very narrowly lost out by 0.57 per cent in the 2011 Presidential Election and was not able to contest in the subsequent presidential election in 2017 due to late changes to the rules for the contest.

He announced during campaigning that he would reject the NCMP seat if it were offered to him.

The 2020 General Election saw the PAP losing another GRC to the WP.

The incumbents in Sengkang GRC were defeated by a young WP team which did not have any experienced legislators and had little electoral experience with only He Ting Ru participating in the 2015 General Election.

The PSP had fielded 24 candidates — the largest slate among opposition parties. The WP only contested in 20 seats. With 10 elected seats going to the WP, the resulting two NCMP seats were offered to the PSP, which went to Leong Mun Wai and Hazel Poa.

True to his words, Dr Tan did not take up the position though he was eligible, after leading his West Coast GRC team to a best performing result among unsuccessful opposition candidates.

The increase in the maximum number of NCMPs did not seem to benefit the PAP again. Other issues such as the handling of the pandemic and the increased presence of credible opposition candidates had swung the support to the opposition.

As with the other two general election campaigns, this author also did not find any interest by voters he had met about the NCMP issue during campaigning.

Customers can apply the following code - MSNCMP20 - for 20 per cent off until Jun. 30 2025. The code is valid only on the World Scientific Webstore.

Top left image via World Scientific, right image by Mothership

MORE STORIES