It took two whole hours after I first met Emily Ho before the extent of her illness became clear.

On a sweltering Saturday afternoon, we’d met at the void deck of the Bedok HDB block that Ho lives in with her parents and sister, and for the better part of 120 minutes, the 29-year-old shared with me what it was like to live with a rare genetic disorder called Pompe disease.

Caused by the deficiency of an enzyme that breaks down complex sugars, the disorder results in progressive muscle weakness.

While the details of prognosis tend to vary depending on the onset of the illness, Pompe disease is currently incurable, and eventually, fatal.

At the end of our interview, I asked Ho if we could take some photos for the article.

She’d need some help standing up, she said; the disease had taken away her strength to do so on her own.

When she’d gotten to her feet — a task that involved someone essentially lifting her from a sitting position — Ho steadied herself on her elbow crutch and took a deep breath.

Receiving her diagnosis

Growing up, Ho used to put her frequent falls and tumbles down to a general state of clumsiness.

“I think I conditioned myself to think, ‘Oh I’m not a sporty person’,” she said with a laugh, recalling the days when primary school physical education lessons seemed mysteriously challenging.

Back then, Ho was already starting to see a gulf in sporting ability between her peers and her; in tasks like running, Ho would struggle for stamina and speed, as well as seemingly tripping over thin air mid-stride.

There were also activities that she felt physically incapable of doing for no discernible reason, a malaise that prompted some classmates to accuse her of malingering.

“I knew that I wasn’t faking, you know? I knew that there were certain things that I couldn’t do. But the people around me didn’t really believe me.”

It wasn’t until secondary school, that a PE teacher suggested Ho should see a doctor, initially suspecting that the falls were due to a lack of equilibrium.

By that point, her mother had grown concerned too that something may be amiss with her 14-year-old daughter.

After a check-up at a polyclinic, a doctor declared that Ho was fine — “because I look so normal what,” she quipped.

“But my mother insisted, ‘if there’s nothing wrong with her, how come she still falls down so frequently?’ So then the doctor referred me to some specialists.”

The next few months of Ho’s life passed by in a blur of testing.

They involved visits to the hospital for neurological tests, blood tests, genetic testing, and eventually, a muscle biopsy.

And at the end of it all, Ho sat down in her doctor’s office and was delivered the news.

“He told me my muscles would weaken over time. He told me that (there’ll come a time) when I won’t have the strength to walk and will have to use a wheelchair. Then he also told me that it will affect my breathing because the diaphragm is also a muscle.”

“Right from the start he told me there was no cure,” she said.

“I just brushed it aside”

Ho described a range of emotions when reflecting on the moment she’d received her diagnosis.

Understandably there was fear and sadness, but somewhat counter-intuitively there was also a sense of comfort.

“I got the diagnosis, you know? So it kind of told me that, eh, I’m not faking this. I’m not faking all the things that I cannot do,” she explained.

But ultimately, all her feelings gave way to a sense of indifference and, perhaps, detachment.

I imagine there must have been a certain surrealness — or maybe even disbelief — to finding out that you have a condition so rare that it only affects one in every 40,000 births.

As of 2021, KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital had only seen four cases of Pompe disease in the last 15 years.

There was also the unfortunate happenstance of both her parents being carriers of the Pompe disease gene.

“So lucky, lorh, the both of them come together then I’m the 25 per cent chance,” Ho chuckled.

Yet the biggest contributor to Ho’s indifference to her illness was the fact that treatment seemed out of reach.

Individuals with Pompe disease can rack up medical expenses in excess of S$500,000 per year; these were costs that Ho’s family simply did not have the finances to meet.

“Honestly, I just brushed it aside,” said Ho, on her diagnosis.

“I just thought that I’ll try and live as long as I can. I didn’t know how this disease will progress mah, so I’ll just continue.”

Ho with her younger sister, circa 98. Image courtesy of Emily Ho.

Ho with her younger sister, circa 98. Image courtesy of Emily Ho.

The “unseen” nature of Pompe disease

At first, continuing wasn’t hard.

After all, progressive muscle-weakening isn’t exactly something that is outwardly obvious, at least in its early stages; in the immediate aftermath of Ho’s diagnosis, nothing really changed.

However, slowly but surely, the disease took its toll.

By the time Ho enrolled into Singapore Polytechnic, where she studied visual effects and motion graphics, navigating steps and getting up from a sitting position was starting to pose a challenge.

Apart from the physical difficulties associated with the ailment, the “unseen” nature of Pompe disease came with a set of social challenges.

Ho recalled the time before she started using a crutch, when traversing the curbside gap while boarding a bus, was daunting.

“Sometimes the driver doesn’t park that close, and it's a challenge. I’ll just miss the bus lorh. I won’t take it and wait for another bus.”

Getting off the bus was slightly different. If it hadn’t parked close enough to the curb for her to get off, Ho would have to explain her predicament to the driver and ask if they could accommodate her.

Ho once had to explain herself to the same driver on consecutive days.

“I was so paiseh (embarrassed). She said to me, ‘You don’t lie to aunty hor. You look okay, why you want to lie to aunty to trouble me?’”

“That was one incident. But I also understand because it's not easy to see (that I have an illness),” Ho mused.

The elbow crutch she now uses serves both as a mobility aid and a sign to passersby that Ho may require assistance.

Early diagnosis and treatment are important

It was one of Ho’s friends that eventually convinced her to try and secure funding for treatment after she’d shared about the insurmountable costs associated with it.

The conversation prompted Ho to write to Sanofi, the pharmaceutical company that developed an enzyme replacement therapy for Pompe disease.

That got the ball rolling on funding and for the past six years, Ho has been going to Changi General Hospital every two weeks for treatment, which involves being hooked up to an intravenous infusion for four to five hours.

Reflecting on the five to seven years after her diagnosis and prior to that conversation, Ho says she didn’t think she would be able to get any help, given what she knew about the cost of treatment, and a sense she got from her doctor — that there were no other good options, apart from somehow finding the money.

“I feel that at the time, they were giving me a dead end lorh. So I felt that I couldn’t do anything else, so I just accepted it.”

The disease is still not widely known, but Ho sees that there’s more awareness of it these days, and with awareness, a higher chance of early diagnosis and treatment.

Her message to anyone in her position is simple: “I would say they should get treatment as early as possible.”

This is especially important as enzyme replacement therapy does not cure Pompe disease or reverse its impact, though it is effective in slowing down the illness’ progression.

The treatment has helped Ho since she started on it; she told me that it is common for her to feel like she has more energy in the weeks that follow treatment.

And as for funding — a major obstacle for Ho back then when she was first diagnosed — things have changed too.

Since November 2019, treatment for Pompe disease is covered by the Rare Disease Fund, a charity established by the Ministry of Health and Singhealth. With the Rare Disease Fund established, treatment initiation time can be shorten as the fund helps patients to be on treatment as early as possible.

The need for adequate support

Ho’s very first session of enzyme replacement therapy, which began in 2015. Image from Emily Ho’s Instagram page

Ho’s very first session of enzyme replacement therapy, which began in 2015. Image from Emily Ho’s Instagram page

The difficulties that Ho experienced in her adolescence impressed upon her the importance of having adequate support — a point she stressed throughout our interview.

“Emotions-wise, you need an outlet,” she explained.

“I feel that there was a need for counselling. Even back then when my condition hadn’t progressed much, but if there was assurance that I had a safe space to go to, someone who tried to understand me, tried to empathise with my struggles, then it would be easier I guess.”

“Not so sad. Not so lonely,” she added.

These days, Ho keeps a small group of friends whom she feels she can trust.

As leaving the house becomes more and more difficult, choosing to meet up with someone isn’t a decision she makes on a whim.

Catching up with a friend requires careful planning, with consideration going to things like how accessible the location is; if it has a drop-off point that Ho can easily navigate; if it has an adequately equipped handicap toilet; and if there are enough places to have a seat.

“I actually have to see if that friend that I’m going out with is someone I’m comfortable with, that I trust them to help me up,” she continued.

“Because if I cannot stand then they will need to carry me up from the chair.”

Despite the graft involved with meetups, Ho told me that making the effort to be present in the lives of her friends remained highly significant to her.

“Of course, I know that they’ll be understanding if I tell them that I cannot be there,” she said.

“But I still try my best to be there, to meet friends, or go to events… people may not see it, but it is my best (effort).”

Ho, who finds joy in visual art and drawing, during one of her treatment sessions. Image courtesy of Emily Ho.

Ho, who finds joy in visual art and drawing, during one of her treatment sessions. Image courtesy of Emily Ho.

“Makes me feel useful”

Ho’s energy is currently being channelled into Ho’s passion for visual art.

Apart from her day job as a graphic designer, Ho spends a lot of her free time hand lettering and doing calligraphy.

“I’m very thankful that I’m able to do art. You can say it’s my happy place — it helps me to escape from my worries for a while” she said.

The activity has given Ho a sense of purpose and fulfilment, after years of self-doubt over how she could contribute to society.

“To tell you the truth, being able to do this — drawing and creating — makes me feel useful.”

Ho posts her works of art on her Instagram page, a feed filled with beautifully drawn hand-lettered creations, many taking inspiration from Bible verses or inspirational quotes.

Her obvious talent and skill were more recently given recognition by her inclusion in the last three volumes of Typism, an Australian-based hand lettering community that publishes an annual compilation of work by artists from around the world.

“It’s quite an achievement, honestly,” said Ho reflectively.

“I’ve always felt that I’m not good enough… so when I get recognised like this, it does feel good.”

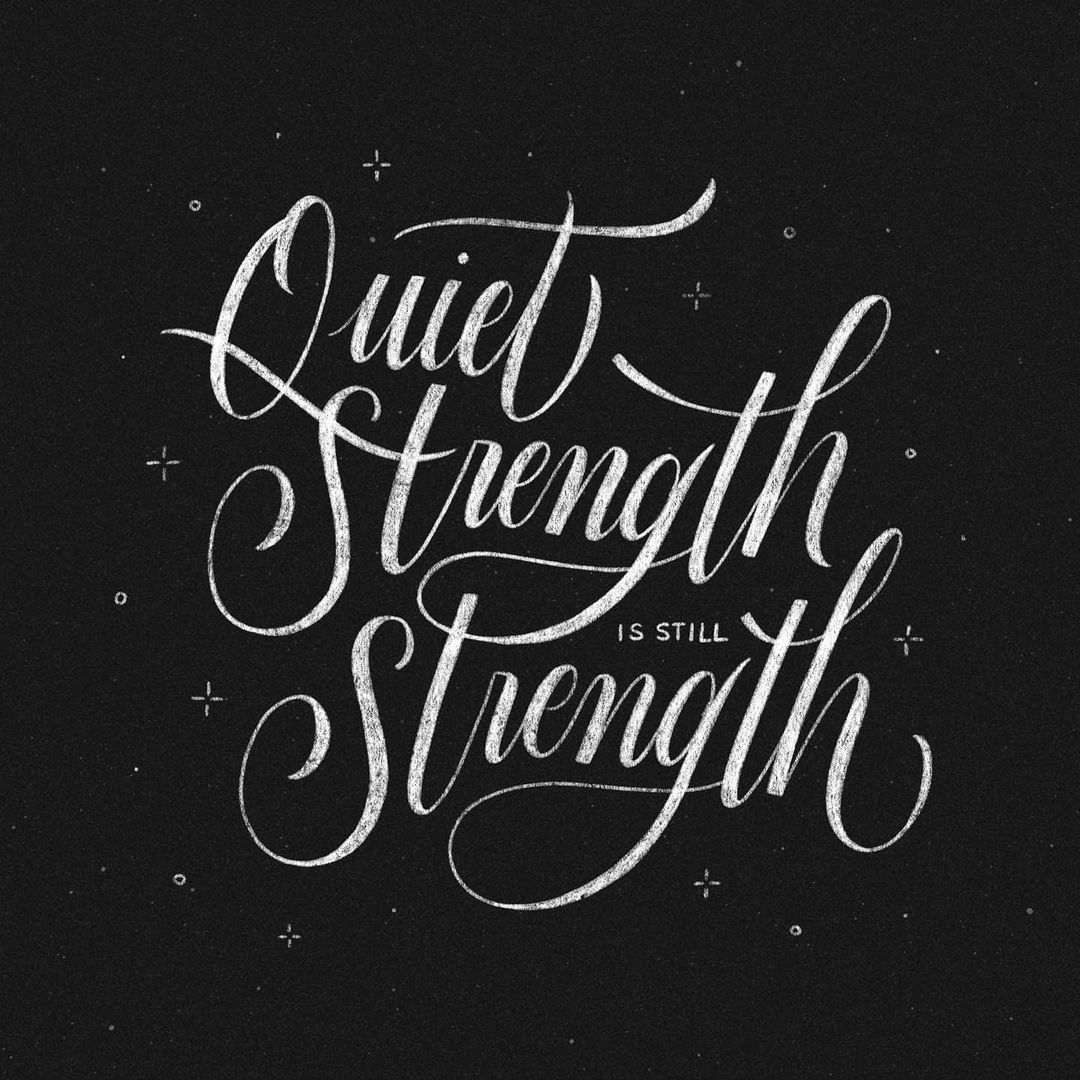

“Quiet strength is still strength”

Image from Emily Ho’s Instagram account

Image from Emily Ho’s Instagram account

The design that featured in the latest volume of Typism’s book involved a quote that Ho has found particularly resonant of late: “Quiet strength is still strength”.

It’s a simple statement that appears to have been coined by fellow visual artist Morgan Harper Nichols, but has become a soothing mantra for the daily struggles that Ho experiences.

“It kinda comforts me (by telling me) that the amount of inner strength and effort it takes for me to show up and keep going every day — that I don’t always share with others, and that not everyone might see — is still valid and not in vain.”

I couldn’t help but feel that Ho’s statement stood as an antithesis to a society where value and admiration often scurry towards what can be seen and can be easily quantified.

“Every kind of effort is valid even if no one sees or acknowledges it,” added Ho to emphatic effect.

At the end of our interview, as we got ready to take some photos, Ho — now on her feet — took a few steps towards me.

It was at this point that I caught a glimpse into how challenging life must be for the plucky 29-year-old.

Her first steps appeared somewhat awkward as she stretched her legs having been seated for the past two hours.

There was a tiny wobble in her gait and Ho took a second to steady herself.

I watched as she breathed in and tightened her grip around the handle of her elbow crutch.

In that moment, I can only imagine that Ho was drawing from her deep well of internal strength — not the kind found in muscles that fade with age; but the sort rooted in the human spirit, that comes hand in hand with a steely resolve to make the most out of life, no matter the circumstances.

Rare Disorders Society (Singapore) is a non-profit patient advocacy group established in 2011 and aims to create awareness about various life-threatening rare diseases.

It also advocates for the needs of patients and their families. Find out more about Rare Disorders Society (Singapore) here.

This awareness piece was brought to you by RDSS, and it reminded the writer to never assume what someone is going through.

Top image by Andrew Koay

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.