One of the first cases that Ponnarasi d/o Gopal Chandra handled as a reintegration officer with the Singapore Prison Service involved a single parent who was serving out the tail end of her prison sentence on a supervised community-based programme.

The supervisee, who had been reunited with her family at home, had just started work, only to suddenly go missing one day.

"I think, for us, as reintegration officers it's important not to judge and [...] jump to a conclusion," the 37-year-old — who is known as Ponna — says.

In some cases, those who went missing had actually ended up being inadvertently hospitalised, she explains.

Which is why, when her supervisee finally picked up the phone after almost three hours of calling, the first thing Ponna asked was, "Are you okay?"

As Ponna found out, the supervisee had been facing a lot of pressure from the expectations placed on her by family members.

While in prison, she had come up with a plan in which she would work toward repaying bank loans, which she had kept secret from her family.

However, when she returned home, she found that her ex-husband expected her to take on a more active role in parenting their two children, while her aging mother's medical needs exacerbated her financial situation.

Ponna explains that her initial "ideal" plan had not taken into account these pressures.

After several months of trying to work things out, she was eventually "unable to cope anymore," and eventually opted to drop out of the programme and return to prison.

As Heidi Tan, 25, a correctional rehabilitation specialist, explains:

"In a way, prison is an artificial environment. In prison, you don't have a lot of the real challenges that you would have outside."

But Ponna's encounter with her supervisee encouraged her of one thing:

"If we didn't have the rapport with them at the onset, she wouldn't have even bothered to return my call or even come back to share."

To Ponna, the episode emphasised the importance of being genuine in her interactions with supervisees — a recurring theme in her 17 years working in prisons.

"If you are genuinely willing to help them, they are willing to share. So far, that's what I have seen in my cases."

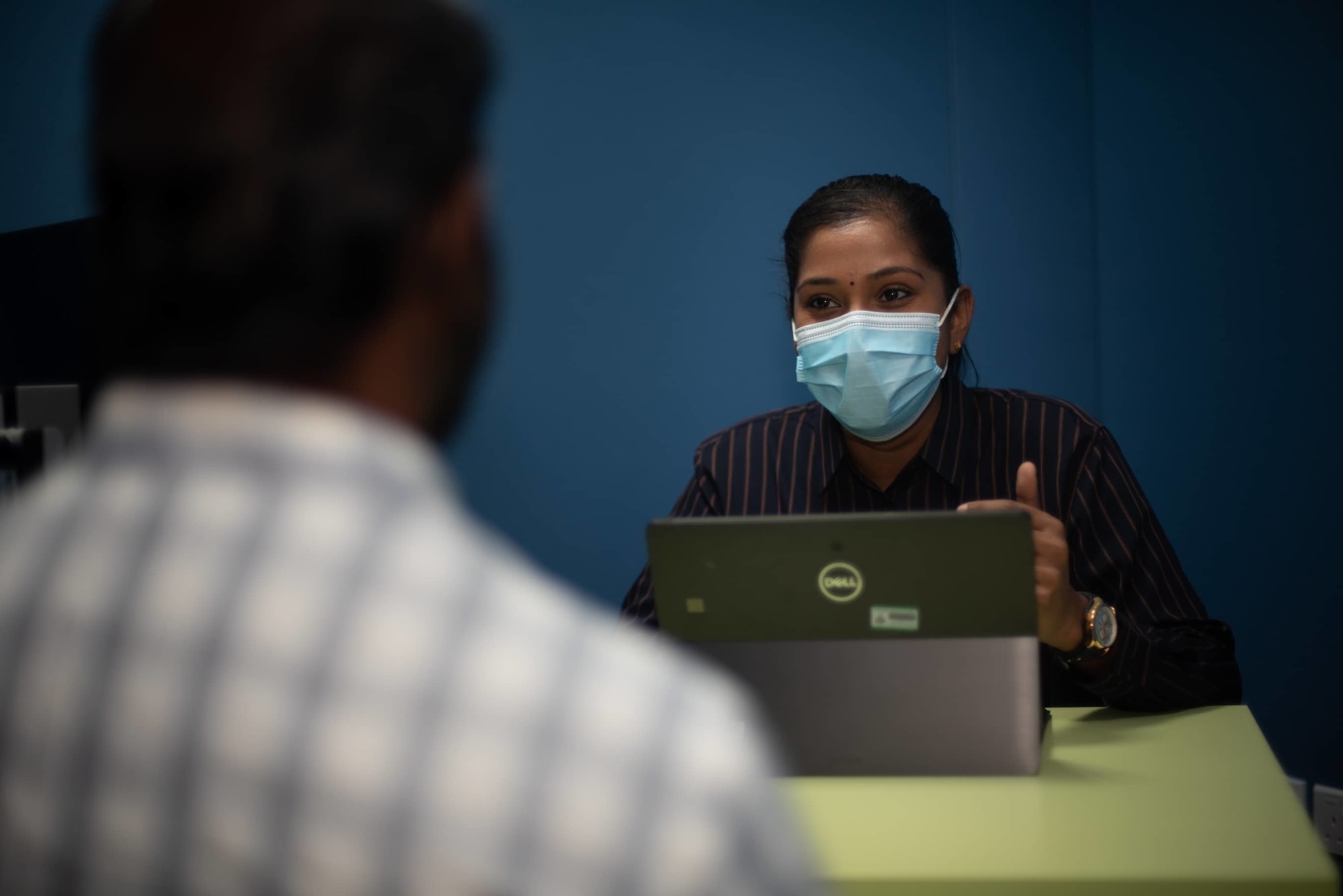

Ponna in a counselling session with a supervisee. Photo by Singapore Prison Service.

Ponna in a counselling session with a supervisee. Photo by Singapore Prison Service.

Tan shares a similar experience with an inmate who thanked her after a one-on-one counselling session.

It was unexpected because, as far as she could remember, he was quiet, sullen, and disengaged during the programme.

"Did I do anything for you?" she blurted out, incredulous. "Because you didn't share anything with me. And I don't know how I could work with you."

The participant, as it turns out, had been prompted by Tan's probing to reflect on his own habits when facing problems.

"He would just isolate himself," says Tan, causing others to stay away from him, which allowed him to forget about his troubles.

He told her:

"Even though I kept trying to avoid my problems and avoid opening up and sharing, you never stopped trying to reach out to me."

Tan with one of the inmates. Photo by Singapore Prison Service.

Tan with one of the inmates. Photo by Singapore Prison Service.

It's telling that Tan cites this particular episode as "the first time" she felt that this was a job that she could do — not because of her academic qualifications or the soundness of the programme, but simply a moment of real human connection.

This is not to say that officers' qualifications and prison programmes are unimportant; Tan explains how her background in psychology is complemented by colleagues who bring in social work expertise.

Psychology is focused on the individual, she says, while social work is about systems.

"So when you kind of mesh these two disciplines together, it makes sense because we are working with the individual within the system.

And so having these two different perspectives helps us not to lose focus of what we can do to make a change."

Changing someone's mind, or helping them to change their mind?

There is an important distinction to be drawn between trying to change someone's mind and helping them to change their minds.

Tan emphasises that change has to come from the inmates themselves, and cannot be imposed on them because of the officer's personal beliefs.

Photo by Singapore Prison Service.

Photo by Singapore Prison Service.

Values, Tan says, are subjective after all. "It doesn't mean that because I'm the counsellor my values are objectively correct," she says.

Someone who has been stealing to support their family may ultimately be doing so because they value being able to provide for their loved ones, for example.

Her role, Tan says, "is more about trying to help them see that there are other ways to achieve their values," instead of simply trying to convince them that they should change.

After all, she adds, "nobody really likes to be told what to do."

Making use of shared experiences

Much of the process of rehabilitation has to be led by the ex-offenders themselves. The officers' role is to facilitate, and guide them along, Tan says.

After all, Tan says, "we're not the experts, they are the experts in their own lives, their own journeys, and they know best the struggles that they have."

For example, when counselling those trying to overcome drug addiction, "it's not about telling them, 'Hey, this is wrong,' because they already know that."

Instead, Tan says, the focus is to help them develop their own strategies.

"Like for example, let's say [you're] outside, you are triggered in a certain situation, can you notice your warning signs? Can you use any coping strategies on the spot to regulate your emotions so that you can make a better decision?"

Tan often sees herself playing the role of a facilitator in group counselling sessions, where inmates can share their experiences with one another.

"They're not going to believe when we say, 'oh, if you try this, it will work,' because we don't know what it's like.

But they will believe it when someone else who has been in their shoes can tell them that 'this worked for me, you might want to try it as well.'"

Tan shares the story of an inmate who signed up for the Gang Alternative Programme, a support group for those who have renounced their gangs and are seeking a different lifestyle — both during and after their time in prison.

He told her that he had been introduced by a fellow inmate from a previous batch, who shared his experience and recommended it.

This initially took Tan by surprise, she says, but now she has come to realise that this was to be expected from an inmate who had successfully internalised "the reason or motivation for change".

To Tan, being able to see this "ripple effect" in action was hugely encouraging.

Ponna with a supervisee. Photo by Singapore Prison Service.

Ponna with a supervisee. Photo by Singapore Prison Service.

Getting family onboard

"You know, that lifestyle that they have had all these years, there is something beyond that, [but] how do we actually push them to see?" Ponna wonders aloud, her experience notwithstanding.

After all, every person they counsel is different, and will require a different approach. Some approaches require more than just the efforts of supervisor and supervisee.

Ponna explains that the default arrangement is for her to work mainly with her supervisees, leaving it to other organisations such as the Ministry of Social and Family Development (MSF) to work with the families.

However, in one case, Ponna needed to get a family's acknowledgement in order for one of her supervisees to be allowed to go back home, given his good progress at a halfway house.

Alas, the supervisee's wife was "not really convinced". After all, the supervisee was a repeat offender.

On the other hand, the supervisee's daughter was supportive of her father coming home, though her mother's resistance meant that Ponna could easily have indicated that it would have been a "clear-cut case" for her to indicate that the supervisee was "not supported by the family", and closed the case.

However, in Ponna's opinion, moving back home would be "a more ideal situation for him, because I think it gives affirmation to his own progress."

Yet, she was not in a position to be making promises to his family.

"I wouldn't give, like, an assurance to the family, 'oh, he's going to change, he's not going to reoffend... he's going to be the perfect man,' I can't do that."

Instead, Ponna reassured the family of the support available, if anything in the supervisee's behaviour suggested that he was going back to his old ways or doing anything that made them uncomfortable; letting them know that they would not be alone in the process.

As a final assurance, she gave the wife a direct line to call — her own contact number.

While Ponna acknowledges this as a case where she did go "above and beyond" the scope of her duty, she quickly adds that what she did was only "slightly" more than required of her.

Struggles and failures

Success stories aside, both Tan and Ponna have had their fair share of struggles, and even failures.

The rehabilitation of a person, Tan says, can sometimes feel like an uphill battle.

"I guess in a way, when you talk about change, right, it sounds so positive. It sounds so like, 'yeah, everybody should want to change.'

But if you think about what you're asking of a person actually it's to leave behind friends you've known since you were young, leave behind security of that kind of money that you get from doing illegal things. It is quite a big thing to ask of them; to change their lives."

There will thus be ex-offenders who cross paths with Tan and Ponna at a time in their lives where they are not quite ready to leave behind their old lifestyles and ways of thinking.

Ultimately, Tan says, they just have to acknowledge that "change is really a process that does not happen overnight."

"Sometimes, you feel like if you give 100 per cent, you also want to see results. But it's not like that with people, you know? You can't expect that of somebody.

Tan says that dealing with such cases, it is helpful to remember that sometimes, change might still take place "much later down the road".

What happens when a supervisee re-offends?

How might prison officers be affected on a personal level, because of all of this very real and very emotional human "drama" that they have to deal with on a daily basis?

Tan solemnly recalls cases where supervisees who completed programmes with her ended up reoffending, and landed back in prison.

"It's very difficult because you really want to root for the person, you really want them to succeed when they're outside," Tan says.

But she reminds herself that while change is a process, it's often not a linear process.

Instead of classifying those she works with according to "black and white success or failure", Tan says that she's learned that "it's really about the journey of learning and growing."

"If they're motivated to change, they will keep going, and then so should I."

Ponna explains that in her first years on the job, she would take it very personally "when a case fails".

She has, however, seen the importance of separating her personal opinions and emotions from her professional obligations.

With experience, Ponna has come to realise that there could be other factors which kept them from making the right decisions, even after she has done all that she can for her supervisees.

"It's more important for me to identify, how can I close these gaps that they have? Instead of, you know, putting it on myself."

Ponna speaking with a supervisee over video call. Photo by Singapore Prison Service.

Ponna speaking with a supervisee over video call. Photo by Singapore Prison Service.

Misconceptions about rehabilitation

As we round up the interview, Ponna shares an observation about how prison officers, and their work with ex-offenders is viewed by the public.

She recalls with some amusement the changing perception of prison officers over time:

"Years back, they always have... scary stories, like, prison officer are very cold hearted... that [a] prison officer is somebody who is scary, who don't talk, who don't smile."

However, that stereotype is evolving, Ponna says, due to more public awareness of what's happening in prison.

Today, "[members of the public] view rehabilitation as a softer approach, which is actually a misconception," she says.

Ponna explains that regardless of how public sentiment changes, rehabilitation work must go "hand in hand" with the deterrent effect of punishment.

Neither objective can be allowed to overshadow the other, she says. "If you simply put the person in prison and send him out, nothing changes, so he's going to continue reoffending," she adds.

But to reduce the chance of reoffending, "we need to do something with them. So that's when rehabilitation actually comes in."

Tan, on a similar note, says that "rehabilitation on its own can only do so much."

To Tan, the work on rehabilitation done in prison and in community-based programmes is one step in the process toward the ultimate goal of reintegration.

"We try to develop their capabilities, to increase their motivation to change, [and] people can get there.

But when they are out in society, they also need people to give them a second chance so that [they] can actually find opportunities, [they] can actually get resources to sustain the change."

Related stories:

Stories of Us is a series about ordinary people in Singapore and the unique ways they’re living their lives. Be it breaking away from conventions, pursuing an atypical passion, or the struggles they are facing, these stories remind us both of our individual uniqueness and our collective humanity.

Totally unrelated but follow and listen to our podcast here

Top photos by Singapore Prison Service

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.