The General Election of 2020 (GE2020) is upon us.

It's an exciting time, with politics and politicians now the talk of the town.

However, there might be some conversations that fly over your head, especially if you're a first-time voter. If that's the case, we're here for you.

These are the nine need-to-know terms that will have you looking like the political expert in any conversation:

1) Mandate

In technical political speak, a mandate is the authority granted by a constituency to its elected officials to act as its representative.

More generally, having “the mandate of the people” refers to a political party having a clear sign of support from Singapore’s citizens to enact its policies and plans. In a democracy (like Singapore) you get a mandate by winning an election.

The term has been trotted out on multiple occasions of late when referring to GE2020 and the Covid-19 pandemic.

For example, on Mar. 27, PM Lee Hsien Loong said:

”I think that we have to weigh conducting an election under abnormal circumstances, against going into a storm with a mandate which is reaching the end of its term. We have to make a decision on that. I would not rule any possibility out”

Chan Chun Sing — according to Bloomberg — said the following on May 20:

”We would like, when the opportunity arises, to have a strong mandate because the challenges that we are going to face in the coming years will indeed be the challenge of an entire generation.”

2) Manifesto

Political parties usually have a purpose for existing. Apart from getting into power, they have policies that they want to introduce and goals to achieve for the constituents they will represent. These are plans and aims are usually published in a document called a manifesto.

For example, the Workers’ Party’s manifesto from GE2015 can be read here.

In it, they expounded on some of their policy proposals, such as improving healthcare affordability by enhancing subsidies for preventive primary care.

Reading a party’s manifesto gives you an idea of what that party will do in Parliament if you vote them into power.

3) Swing

This election, there will be many battlegrounds revisited. Many opposition parties will be hoping for a better result than what they got at GE2015 and incumbents will be hoping to stretch their winning margins further.

The proportion of voters that change their decision from one election to another is called the swing — as in these voters swung from supporting one party to another.

Monitoring how many the votes swing between elections gives you an idea of how sentiment on the ground might be changing.

For example, GE2015 saw the PAP improve on their GE2011 result in Holland-Bukit Timah GRC (from 60.1 per cent of the vote to 66.6 per cent), earning a 6.5 per cent swing towards the ruling party among voters, according to results published by the Elections Department (ELD).

4) Popular vote

The popular vote refers to a way of voting — where every single person in a constituency or country gets to vote. The party who garners the most votes in the country is said to have won the popular vote.

This is in contrast with, say, the U.S. presidential election where a president is chosen by “electors” through a process called the Electoral College.

In GE2015, the PAP got a total of 1,576,784 votes, winning 69.9 per cent of the popular vote, according to Singapore Elections.

However, in Singapore’s electoral system, the popular vote is not used to determine the winner of an election; it is theoretically possible for a party to lose the popular vote and still win an election.

To give an extreme, unlikely example, one party could narrowly win most of the seats in parliament by one vote, and then lose a few by landslide — this would see them win the election (as they have won the majority of seats) but lose the popular vote.

Nevertheless, the popular vote remains a useful metric to gauge the overall sentiment of Singaporeans towards the ruling party.

Image by Element5 Digital via Unsplash

Image by Element5 Digital via Unsplash

5) Spoilt votes

GE2015 saw 47,315 votes that were deformed in a such a way that they could not be counted as valid. These votes are known as spoilt votes and, according to this paper published on IPS Commons, have consistently made up between 2 and 2.9 per cent of votes casted over the last 48 years.

Why would a Singaporean spoil their vote? Well, one reason could be a dissatisfaction with all the options available — they aren’t inspired to give support to any of the parties contesting in their constituencies.

Back in 2015, we actually asked seven Singaporeans why they might have spoilt their votes. Here's what they had to say:

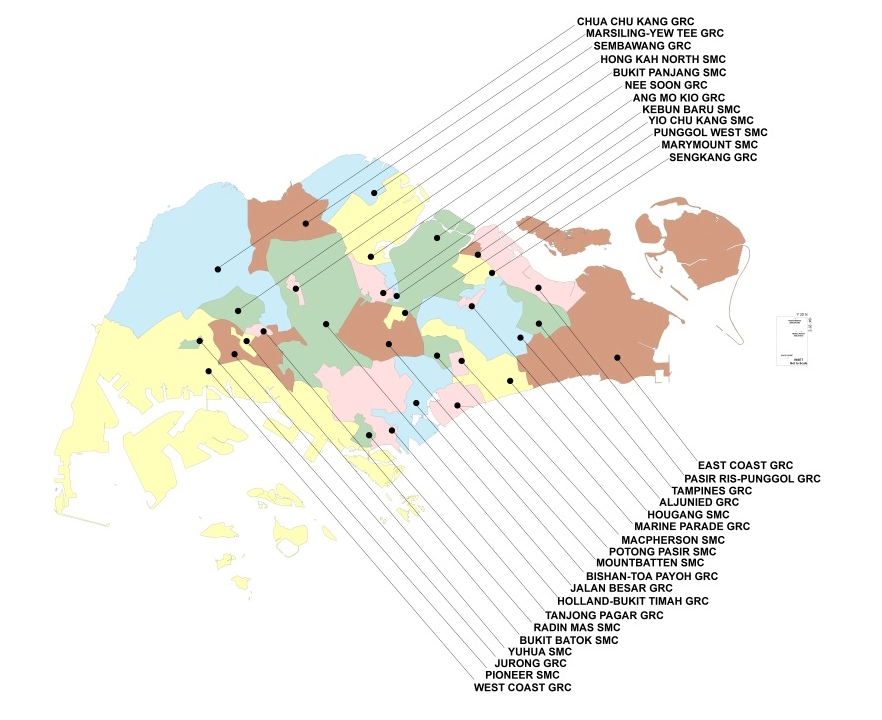

6) Electoral divisions

In short, electoral divisions refer to the constituencies that Singapore is split up into during elections.

It is within these divisions that politicians campaign for votes, so that they can win a seat in Parliament and represent that particular constituency.

For example, Aljunied GRC, is an electoral division represented by five seats in Parliament that were won by the Workers’ Party during GE2015. Thus, the interests of the people living within Aljunied GRC are represented in Parliament by the Workers’ Party politicians who won those seats.

Broadly speaking, electoral divisions are drawn according to geographical location. However the boundaries of these divisions are regularly revised to reflect population growth and shifts, according to the Elections Department of Singapore.

These boundaries are recommended by senior civil servants with “relevant domain knowledge”. These civil servants make up what is called the Electoral Boundaries Review Committee.

The latest report by the committee can be read here.

Among its recommendations were the creation of four new SMCs (Punggol West, Yio Chu Kang, Kebun Bahru, and Marymount) and one GRC (Sengkang GRC).

These recommendations were accepted by the government and will be implemented for GE2020.

Image screenshot from ELD

Image screenshot from ELD

7) Three-cornered fights

When a constituency sees three parties (or candidates) competing for the same seat, we get a three-cornered fight.

In GE2015, Radin Mas SMC experienced this when the PAP’s Sam Tan Chin Siong, went up against the Reform Party’s Kumar Appavoo, and independent candidate Han Hui Hui — famous for her "return our CPF" refrain.

It ended up being quite the lacklustre contest with Tan winning 77 per cent of the vote — this is typical of three-cornered fights which are said to split opposition votes.

We did, however, get this infamous moment:

GE2020 will see a couple of three-cornered fights.

Pioneer SMC will see the PAP, PSP, and independent candidate Cheang Peng Wah square off, while Pasir-Ris Punggol will host a contest between the PAP, SDA, and PV.

8) Cooling-off Day

The day before Singaporeans head to the polls, all campaigning has to stop.

This 24-hour period is called Cooling-off Day, which according to the ELD, is a period of silence meant to give voters some time to “reflect rationally on issues raised during the election”.

To give you a sense of what kind of actions are banned, Section 77 of the Parliamentary Elections Act states that the following are not allowed to be worn, used, carried, or displayed by any person or vehicle as political propaganda on Cooling-Off Day and Polling Day:

- Badges

- Symbols

- Rosettes

- Favours

- Set of colours

- Flags

- Advertisements

- Handbills

- Placards

- Posters

- Replicas of a voting papers

Election advertising is also prohibited.

9) Landslide Victory

A party is said to have won by a landslide when they receive the overwhelming proportion of the votes.

Examples of landslide victories were seen in GE2015 at Jurong GRC, where the PAP won almost 80 per cent of the votes, and Ang Mo Kio GRC where the PAP team helmed by PM Lee won close to 79 per cent of the votes.

In fact GE2015 saw quite a few landslide victories, with no less than 15 constituencies going to the ruling party with at least 70 per cent of the votes.

Top image by Kane Raynard Goh

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.