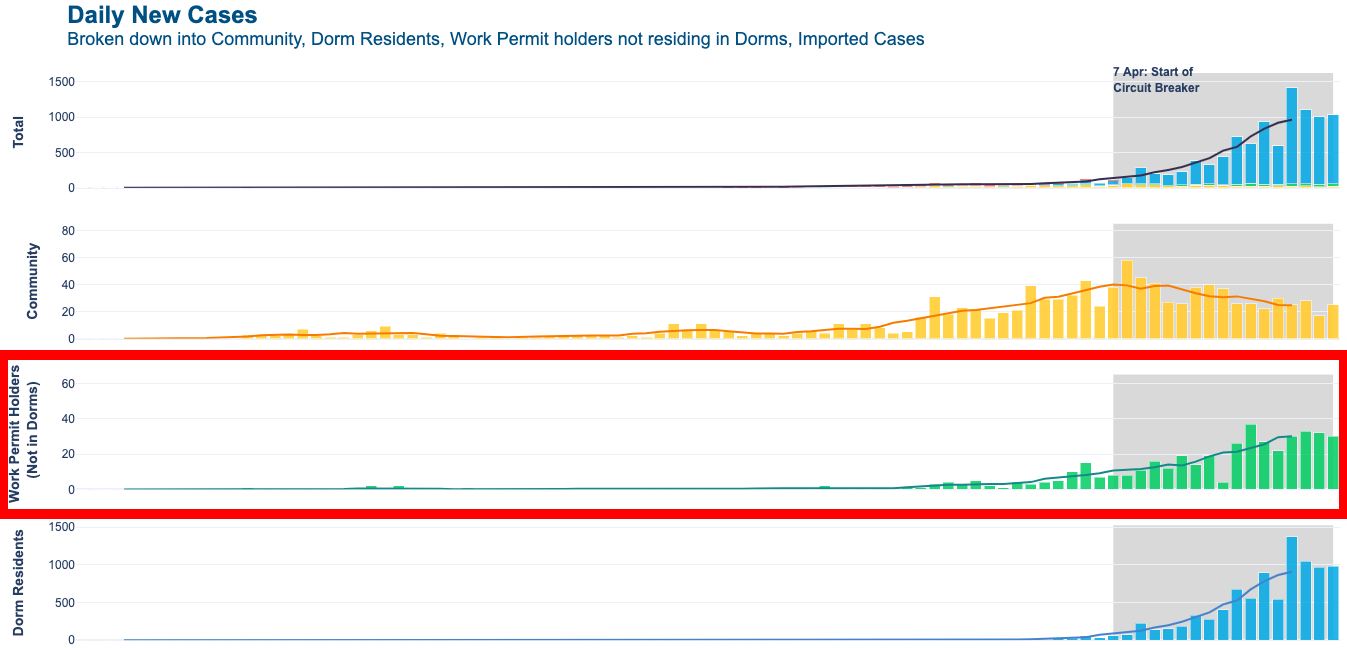

Singapore's reported Covid-19 cases has rapidly increased over the past couple of weeks, with the vast majority of the more recent ones being amongst migrant workers living in dormitories.

The number of cases linked to clusters at dormitories has spiked, going from less than 100 cases at the beginning of April to crossing the 9,000 mark, as of Apr. 23.

Image screen captured from MOH Apr. 23 Situation Report.

Image screen captured from MOH Apr. 23 Situation Report.

The Ministry of Health's situation report on Apr. 23 shows that 9,076 of the country's 11,178 confirmed cases are dormitory residents.

As the situation progressed this month, many have noticed that the Ministry of Health (MOH) changed the way it reports its daily case figures, now categorising them into:

- Local cases in the community,

- Work Permit holders (residing outside dormitories), and

- Work Permit holders (residing in dormitories).

According to MOH, "community cases" consist of Singapore residents and pass holders but exclude work permit holders and dormitory residents.

Prior to this, reported cases had been divided into just two broad categories: locally-transmitted cases and imported cases.

And in line with this, the ministry reports a visible decline in the number of Covid-19 cases amongst what MOH classifies as "in the community", which stands in stark contrast to the rapid rise in the number of reported cases among the migrant worker (work permit) community in these weeks.

So how did the use of this "cases in the community" terminology come about, and what implications does it have on Singapore's relationship with our migrant workforce?

MOH's use of "cases in the community"

The first time MOH used the terminology "cases in the community" to segregate work permit-related cases was in MOH’s Apr. 12 news release.

Prior to that, the cases had been divided into two broad categories: Imported cases and local cases (linked and unlinked).

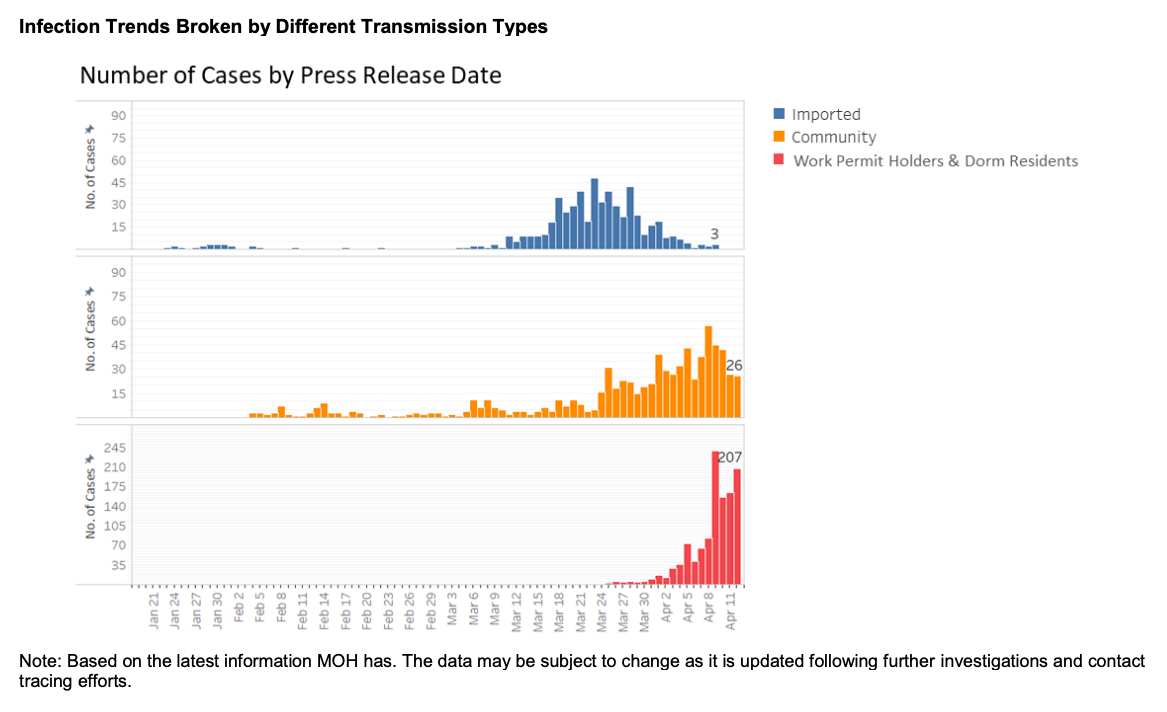

The Apr. 12 news release included a chart tracking infection trends broken down by different transmission types.

The different transmission types were identified as:

- Imported,

- Community, and

- Work permit holders and dormitory residents.

MOH chart from Apr. 12.

MOH chart from Apr. 12.

This was MOH's analysis of the chart:

"As seen from the chart, the number of imported cases rose around mid-March due to the large number of returnees but has since come down to zero.

The number of cases in the community increased following the wave of new imported cases, but there has been some moderation in recent days, in light of the safe-distancing measures that have been put in place earlier.

The number of work permit and dormitory-related cases has also increased sharply, and this is likely to continue going up, especially as we undertake more aggressive testing at the dormitories." (emphasis ours)

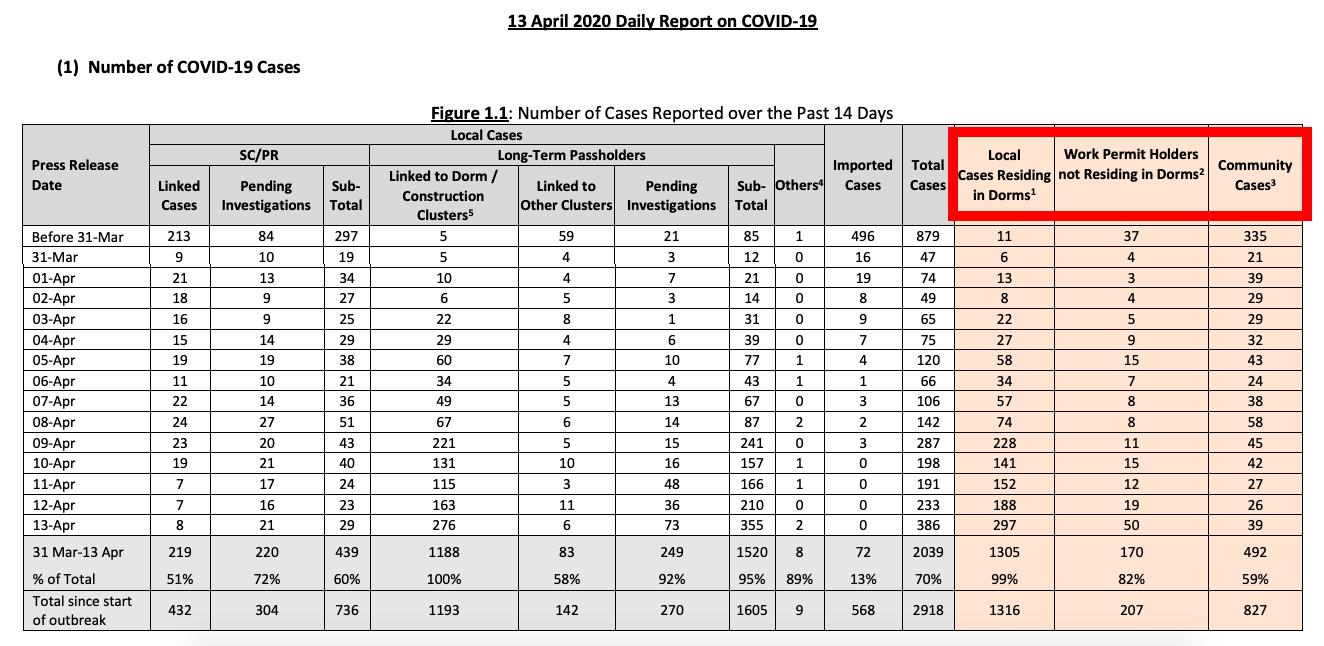

MOH's situation report one day later, on Apr. 13, added an extra three columns to its table of figures, labelling past cases according to these categories:

- Local cases residing in dorms

- Work permit holders not residing in dorms

- Community cases

Then, from Apr. 15, MOH began categorising each day's cases according to the following categories in their press releases:

- Imported cases

- Local cases in the community

- Work Permit holders (residing outside dormitories)

- Work Permit holders (residing in dormitories)

Each day, MOH would give a summary of how each of the categories' cases have been trending.

For example, on Apr. 23, MOH wrote the following about the "cases in the community":

"The number of new cases in the community has decreased, from an average of 34 cases per day in the week before, to an average of 25 per day in the past week.

The number of unlinked cases in the community has decreased slightly, from an average of 20 cases per day in the week before, to an average of 18 per day in the past week."

Meanwhile, the Apr. 23 release noted that the number of cases amongst work permit holders — both those residing in and outside dormitories — had been increasing, with the vast majority of the daily cases being migrant workers living in dormitories.

This, said MOH, was due to "extensive testing" in the dormitories.

Lawrence Wong: "We are dealing with two separate infections"

The shift in the ministry's categorisation of cases came about one week after Minister for National Development and co-chair of the Multi-Ministry TaskForce on Covid-19 Lawrence Wong said at a press conference on Apr. 9 that Singapore was seeing two separate infections:

“When you look at the situation in Singapore, I think it's important to realise and recognise that we are dealing with two separate infections — one happening in the foreign worker dormitories, where the numbers are rising sharply, and there is another, the general population, where the numbers are more stable for now."

Because of the two different situations, said Wong, the situation in the dormitories warranted a different strategy for dealing with it:

"And that's why we need a different strategy, a dedicated strategy, for our foreign worker dormitories, because there is a greater spread of the virus in these dormitories, and there is also higher transmission rates, given the large numbers of workers living in close quarters."

He announced that a separate taskforce, staffed by the Singapore Armed Forces and the Singapore Police Force, had been set up to focus on the dormitory situation.

It seems clear therefore, from a public health and containment policy standpoint, why cases linked to dormitory clusters are tracked separately from other locally-transmitted cases.

(After all, most people in Singapore are not living at least 10 to 12 people to a room, sleeping in bunk beds and with very little personal space.)

Now, for those of you wondering what precisely is MOH's reason for recategorising cases this way, know that we did ask the ministry and will update this article if we hear back from them.

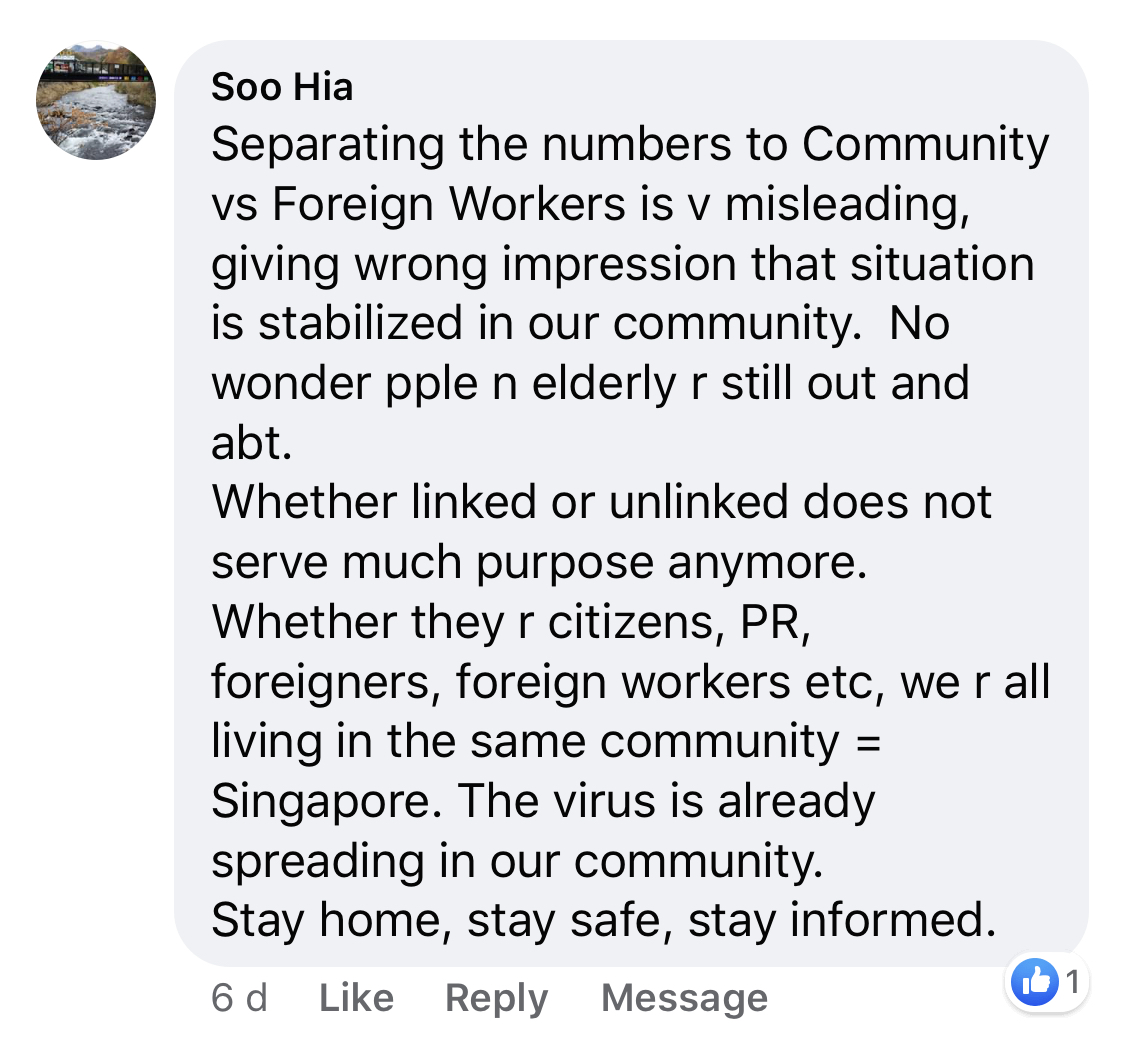

But whatever the official rationale is, the use of the word "community" to describe cases that exclude work permit holders and foreign worker dormitory residents has raised concerns by some here.

Why segregate?

Readers commenting on various media that reported these new categorisations came forward with questions about them:

Others pointed out what is potentially a more concerning effect (or indeed, reflection, given that this was happening earlier than the shifting categorisation), of segregating community cases from work permit cases:

From the start of the Covid-19 outbreak here until the number of cases linked to dormitories began rising at a worrying pace, migrant workers living in dormitories were largely left out of community efforts against the virus.

In an interview with Mothership about a month ago, Dr. Jeremy Lim, who volunteers with migrant worker non-governmental organisation HealthServe, noted that migrant workers were not included in the government's measures to provide masks to every household back in February, for instance:

"They tend to be omitted when we think about public health planning in terms of resource allocation, because they are just a less visible population."

On the consequences of flouting circuit breaker measures

Meanwhile, some have also spoken out to highlight the consequences dealt to work pass holders who flouted Stay-Home Notices (SHNs) and circuit breaker measures.

Work passes were revoked and workers were deported and banned permanently from working here, in cases like the 24 individuals who were found eating, drinking and gathering in the vicinity of Tuas View Square, as well as in the cases of the 89 who had theirs revoked for flouting SHNs.

Local NGO Humanitarian Organization for Migrant Economics (HOME) called the measures "harsh and disproportionate", especially compared with the composition fines issued to Singapore residents in breach.

HOME argued that these standards should be applied evenly across everyone in Singapore, regardless of nationality and residential status.

MOM said that these measures were to "send a clear signal of the seriousness of the offences" committed. More recently, in an interview on Thursday after visiting a dormitory, Minister for Home Affairs K Shanmugam said in no uncertain terms that

"I think the message has to go out very clearly, that if you breach the rules, very severe action will be taken. We want to stop the spread and everyone has to observe the rules."

But perhaps the issue here is more with communication

In its statement about the measures taken against workers found in breach of circuit breaker rules, HOME also expressed concern about whether these new laws and rules might have been communicated sufficiently clearly to workers before they were punished.

"We have heard from numerous workers that communication about various matters has been uneven across dorms. Many of them are experiencing anxiety, confusion and despair as the situation in dorms escalates every day, and are not receiving timely updates about the rules, the number of cases, and the availability of medical care, amongst other things."

As rules applying to Singapore residents at large have also been evolving almost by the day, much to the confusion of citizens as well, even former Member of Parliament Inderjit Singh suggested more straightforward directives — which we do know now are in force:

Have migrant workers ever been part of our community?

Arguably, the fact that Singapore's Covid-19 dormitory clusters have been able to form and be contained in what Minister Wong has been able to speak of as "two separate infections" demonstrates the physical segregation experienced by a majority of the migrant worker population from the rest of Singapore.

It is also worth, at this juncture, noting the longtime, but not often spoken-about, sentiment some Singaporeans seem to have about foreign workers, though.

A feature on Kopi, a local online publication, raises this "not in my backyard" (also known as NIMBY) mindset:

"Singaporeans are fine with their presence and appreciate their contributions, but they rather not have them in their backyard.

In other words, due to perceived reasons like disharmony, invasion of privacy, littering and crime, Singaporeans are mostly against dormitories being built near housing estates."

One incident where this emerged was back in 2008, when residents in Serangoon Gardens petitioned against the construction of a foreign worker dormitory in their neighbourhood.

The Straits Times reported at the time that residents voiced fears to their then-Member of Parliament Lim Hwee Hua that foreign workers would dirty their parks, congest their streets, and violate the children and women in the community.

12 years on, while a host of local initiatives and organisations like Welcome in My Backyard, Migrant x Me, and Vaangae Anna are working to integrate migrant workers into our community, some continue to cling stubbornly to notions that are often flawed and xenophobic.

When it was announced in April that some healthy migrant workers working in essential services would be moved out of their dormitories into vacant HDB blocks in Redhill, some Facebook users made these comments:

The Facebook comments reflected sentiments published in a Lianhe Zaobao forum letter on Apr. 13 attributing the outbreak in dormitories to migrant workers' poor personal hygiene and "bad habits":

The letter was, thankfully, denounced widely, most notably by Minister for Home Affairs K Shanmugam:

The danger of thinking of foreign workers as "them" and residents as "us"

Photo by Sumita Thiagarajan.

Photo by Sumita Thiagarajan.

In an interview with CNA Insider's Talking Point, Dr. Leong Hoe Nam, an infectious diseases specialist at Mount Elizabeth Medical Centre, said that if Singapore's dormitory clusters aren't managed properly, the worst case scenario is that under lockdown, everyone in the dormitories could get infected over several weeks.

If that were to happen, he said, we would have tens of thousands of new Covid-19 cases. It would also not be a good reflection on Singaporeans:

"It doesn't show the compassion which we have as Singaporeans, and it really shows that we are separating the foreign workers as a different group of people, compared to ourselves."

While work permit holders and dormitory residents may not be counted as "community cases" by MOH for the sake of public health reporting, it does raise the question of whether distinguishing migrant workers from locals, residents and long-term pass holders is effective, and if migrant workers are actually a part of the Singapore many of them have helped to build and carry out essential, indispensable tasks in.

It is worth considering how it reflects on us if we see the numbers of cases "in the community" going down and breathe a sigh of relief, thinking "Whew, the main outbreak is in the dormitories. We're still doing okay."

As local academics Teo You Yenn and Ng Kok Hoe wrote recently:

"... the Covid-19 crisis powerfully illustrates the social implications of inequality and sheds light on gaps in the management of our economy and society."

An encouraging development arising from the segregation of cases between those in the community and work permit holders, though, is the numerous ground-up efforts to plug gaps unwittingly left by quickly-enforced measures that employers and dormitory operators, and even government resources, are straining to fully meet.

And there are many encouraging individuals speaking out and stepping up —

- the Sengkang General Hospital doctor reassuring workers in a dormitory that they would be taken care of, for instance;

- calls for others to show their support to foreign workers through small acts of kindness;

- even a donation of 1.3 million reusable face masks to be given to migrant workers and domestic workers.

Many of these Singaporeans certainly realise that the sharp increases in confirmed cases in dormitories suggest an urgent need for help on the ground there, as well as an eventual retrospective review of their living conditions in general.

The Covid-19 pandemic has undoubtedly exacerbated and illuminated existing issues of inequality in Singapore, and how we deal with the issues surrounding migrant workers will certainly speak volumes about us as a society and as a Singapore community.

Mothership Explains is a series where we dig deep into the important, interesting, and confusing going-ons in our world and try to, well, explain them.

This series aims to provide in-depth, easy-to-understand explanations to keep our readers up to date on not just what is going on in the world, but also the "why's".

Top photos via Ministry of Manpower and Getty Images.

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.