Being diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia was actually a relief for Rayner Gooi.

"It was a relief when I took the medication and [the delusions and psychosis] stopped. For the symptoms to stop, you feel your life has just been saved," says the 46-year-old lawyer and artist.

The diagnosis was, finally, the solution to the bizarre hell his life had turned into when he was 26.

Spotting coded messages on television

Meeting Gooi for the first time, I was a little surprised to find that he isn't so different from the next man.

It's hard to tell that he has been living with schizophrenia for the past 20 years. During our conversation, the soft-spoken man is earnest and thoughtful about his answers.

But when he starts dredging up the memories of the delusions caused by his mental illness, Gooi is visibly shaken.

"In terms of the fear, the trauma, and the terror you experienced, it takes years (to recover) because some things you can't forget."

At first, the delusions were innocent enough. Gooi found himself spotting coded messages on the radio and television meant for him alone.

Being "chosen" to receive these special coded messages made him feel special, elated even, at first:

"Hey you're really special. We've chosen you for a higher purpose."

However, the messages became increasingly malevolent within a week.

"We're going to condition you to obey our commands. If you don't do it, we're going to torment you."

"We're coming after you. We're going to come and get you."

"We're going to get you, so you might as well kill yourself. If you don't kill yourself, we will kill your family first then we will kill you."

His delusions felt so real that he had trouble distinguishing between reality and his psychosis:

"When I went out in public, then I felt that people were sending coded messages to me. Or when people behaved weirdly and I thought they were a threat to me."

It got to a point where his delusions started to paralyse him.

He wouldn't eat out of fear of being poisoned. He wouldn't watch television or listen to the radio because he was afraid of receiving threatening messages. He even decided not to go out because he thought there were cameras everywhere observing his movements.

Fearing for his and his family's safety, Gooi told his father about the coded messages and the threats. That was when Gooi senior realised that his son needed medical help and took him to a hospital.

Triggered by the stress

What causes schizophrenia?

To this day, researchers are unable to pin down an exact cause but generally agree that a combination of physical, genetic, psychological and environmental factors makes one prone to developing the condition.

More often than not, a stressful life event can trigger a psychotic episode.

Gooi reckons that his schizophrenia was triggered by the stress of attempting to write an admission paper to a law degree course at Oxford, adding that he had put a lot of pressure on himself at that time to get in.

"There was a lecturer (Joseph Raz) there whom I thought very highly of. I wanted to write a paper that would impress him despite the fact that in terms of law, I had no legal knowledge and absolutely no idea about the subject he was lecturing on."

Perhaps more surprising is the fact that Gooi at that time already had a double major in Literature and Sociology from the National University of Singapore (NUS).

"I love learning. When I was in NUS, it was the first time in my life that I was studying things I was genuinely interested in so I was reading everything I could get my hands on," he says.

His appetite for learning led him to the works of Raz, a political philosopher — particularly his debates on law and morality.

"I bought his books, I read them, and I thought that I had to write a PhD-level, journal-worthy article that would make him go, 'Wow, I want this student.' It really wasn't easy," he says.

That was 20 years ago, though.

"Back then I was very gung-ho. I had a very can-do attitude and I wasn't afraid of anything," Gooi says, almost wistfully.

Gooi says that his schizophrenia could have been triggered by the stress of writing his university admission essay. Image by Ilene Fong.

Gooi says that his schizophrenia could have been triggered by the stress of writing his university admission essay. Image by Ilene Fong.

Recovery and relapse

Gooi's condition is currently being monitored by his doctor at Siglap via monthly check-ups. These check-ups also allow his doctor to adjust his medication dosages (three types in total) so that they continue to help him without interfering in his daily work.

He says his early medications caused drowsiness, and just after being called to the bar, he would fall asleep at work.

"That's not very professional for a lawyer," he adds with a chuckle. Today, he only takes the drowsy medication on weekends.

Being on antipsychotics doesn't eradicate Gooi's delusions and psychosis completely, but any episodes he might experience are now fewer and further between, he says.

"The medication stops most of the symptoms, but it takes awhile for you to come back to reality."

It took a few years after his diagnosis before Gooi dared to tune in to the radio and television, and take public transport again. Gooi also cannot watch films or shows like "A Beautiful Mind" (a movie about the late John Nash, a mathematician who also had schizophrenia, starring Russell Crowe) out of fear that it may trigger traumatic memories.

"You know with your head (that it's not real), but here you still feel it," he says pointing to his heart. "The trauma is still there."

And since schizophrenia is a chronic disease, Gooi cannot stop taking his medication.

A few months after his diagnosis, he stopped taking his medication because he thought he was getting better.

He quickly learned that it was a big mistake when the psychosis and delusions returned with a vengeance a few months later.

"It was basically the same symptoms, just greater amplitude. I was so terrified that when they brought me in to see my doctor, I had to be sedated," says Gooi.

At that point, the paranoia was so severe that Gooi kept himself awake for three days because he was afraid that someone would come get him in his sleep.

That relapse forced him to keep to his medication regimen. "I honestly don't know if I can survive another episode," he says quietly.

Lost clients because of his condition

Some things, though, cannot be solved with medication.

While Gooi's medicine helps to curb what are known as positive symptoms (the presence of hallucinations and delusions, for example), it does little for the negative symptoms (the absence of pleasure or will to do things, or not wanting to socialise).

"I used to stay at home all the time, never leave the house. If I had to work, I'd go to work and then I'll go straight home."

Gooi also shares that he used to be able to take pleasure in being able to draw something spontaneously. Today, he finds that even that doesn't help cheer him up.

And tackling these negative symptoms isn't easy. Not only does Gooi know he has to be very aware of them, he also has to have the discipline to actively work against them — making the effort to go out and meet his friends, for example.

"I know there are bad days when I'm not thinking charitably of people and their motivations and I consciously question myself when I think like that. I tell myself to suspend judgement and wait until I'm thinking clearly."

Recovery is a long journey, one that Gooi has been on for the past 19 years, but he has seen some improvements along the way, especially in the area of socialising with others.

He says he is upfront about his condition with his friends from his Anglo-Chinese School days, and is thankful that he has their support.

These friends, whom Gooi calls his "brothers", often know when to check in on him when he's feeling down.

In that respect, Gooi considers himself pretty lucky. Even when it comes to work, Gooi found that some of his previous employers were very accepting of his condition as long as he did his work well.

He knows his circumstances are not common — many schizophrenia sufferers don't experience this kind of support, he says. Finding supportive, understanding employers and colleagues is a very real struggle for many too.

"Conversations about employment stop as soon as you reveal you have a mental health condition," he says. "That's still true to a certain extent."

Gooi also does not open up about his condition in the professional setting, out of concern that there will be "backlash or repercussion".

Gooi is also open about the very real possibility that potential clients might discover his condition and doubt his ability once they Google his rather unique name — he reveals that he has lost clients because of their perception that he might not be up to the job.

But he still chooses to tell his story, believing it might bring hope to others.

"Someone might see [my story] and realise that he or she can be helped with medication. On the flip side, if I keep quiet, it serves my self interest but then the stigma continues. The reality is there there may be people who commit suicide because of that."

Using art as an outlet

Today, Gooi owns a law firm that helps small and medium enterprises with drafting contracts. He also paints on the side as an outlet for his creative impulses, and as a way for him to cope with the antisocial aspects of his condition.

"You spend so much time alone — you need to do something to occupy yourself with that time, so I figured I'll start painting," he says.

For many, his artwork can be pretty jarring.

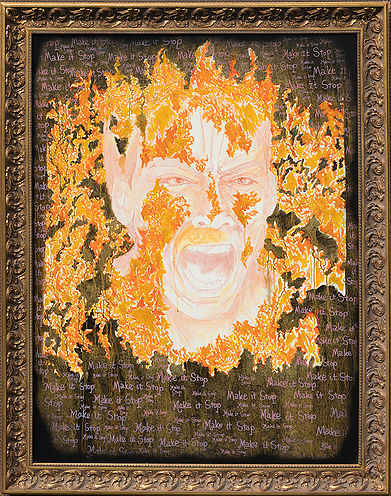

This one, with a man ablaze while the plea "Make it Stop" runs over and over in the background, is titled "Schizophrenic's Scream":

Via RaynerWorks.com

Via RaynerWorks.com

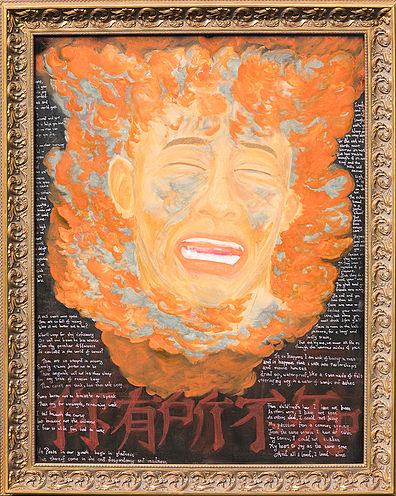

This one is "Serotonin Sadness":

Via RaynerWorks.com

Via RaynerWorks.com

It's tempting to try to attach numerous layers of meaning to Gooi's paintings, but he cautions me against that, insisting that his work is purely visceral.

"I don't think like I want to have a specific message, a lot of it is very visceral. It comes from here," he says, pointing to his heart.

In fact, painting is quite the cathartic experience for him.

In November last year, Gooi put up an art show where he "came out" as a person with schizophrenia. For him, it was a platform to share with his family and friends about mental illness.

Gooi was heartened by the "mostly positive" response to his art show. "I was very touched by it," he says.

"It was something to start the ball rolling, it got me started. It got me used to talking about [my schizophrenia]," he says.

Coming out to talk about his own experiences with schizophrenia is undoubtedly a brave and difficult decision to make. Gooi acknowledges that it might bring backlash, but he wants to do it so that others who are living with schizophrenia will find it easier to identify the problem in themselves and seek help.

"Don't feel paiseh about seeking help. The help is out there. There are people who want to help, and things can get better."

And the search for help, by Gooi's own admission, is a difficult first step for people living with schizophrenia, and his own experience over the past two decades is a testament to the journey to recovery not being at all easy.

"There are still some things that I am struggling with," he admits. "But where there is life, there is hope."

Watch Gooi talk about his experience with schizophrenia here:

Top image by Ilene Fong.If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.