“Remember the beat. It’s ta ti-ti ta ti-ti ta! Let’s try it again okay?” booms a voice from the front of the room to a group of 10 adults, each standing behind a knee-high drum and holding a pair of drumsticks.

The students repeat the pattern, and though it isn’t perfect, it’s certainly an improvement on their previous attempt.

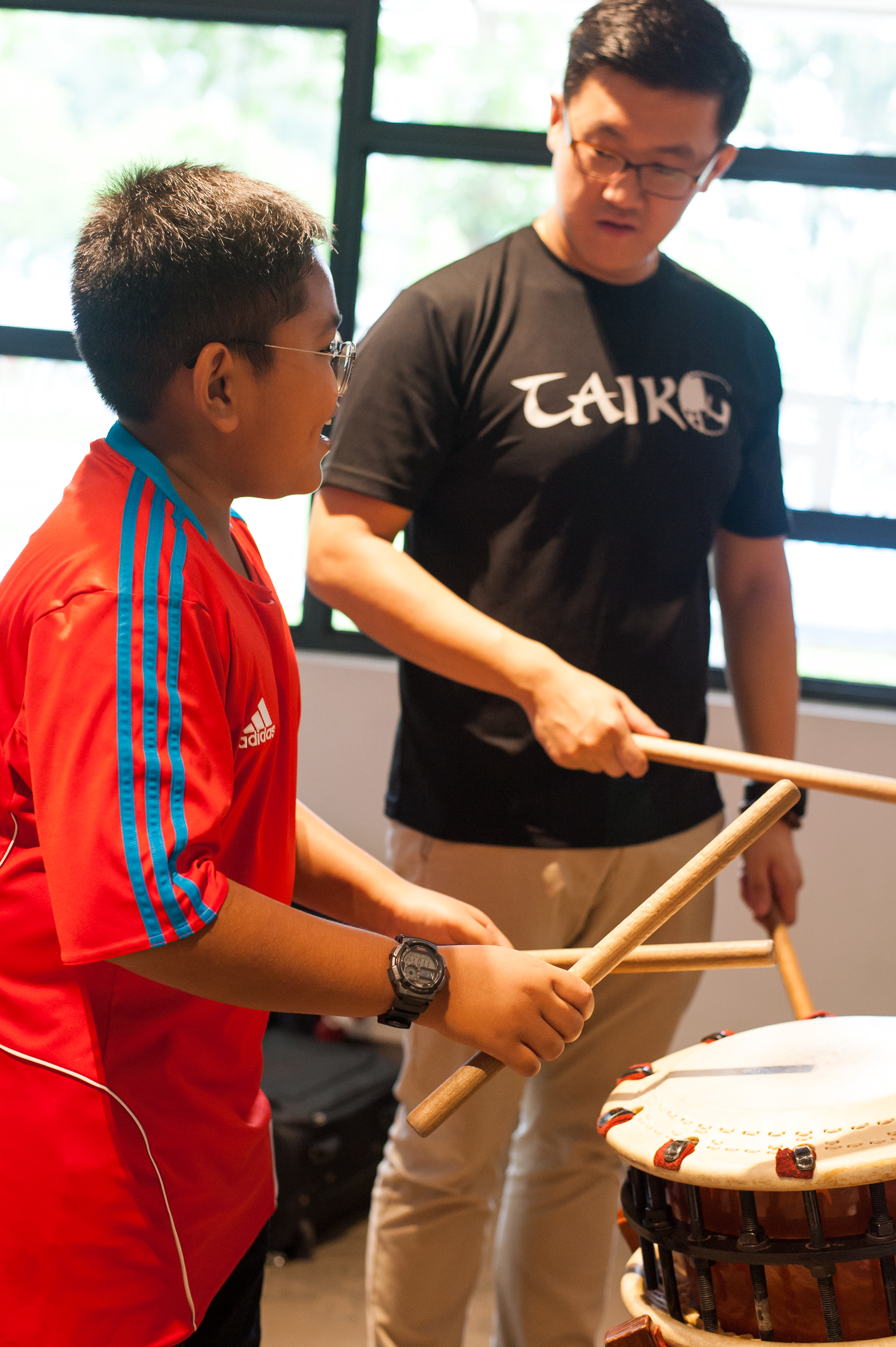

In one corner of the room, giving individual coaching to one of the participants in the class, is 29-year-old Wang Junyong.

He’s the founder of Mangrove Learning, a social enterprise that uses drumming — specifically the traditional Japanese art form of taiko drumming — as a tool to engage and build confidence in people.

(If you've never heard of taiko drumming, you can check out a performance of it here: )

On the day I meet him, Wang and a Mangrove volunteer instructor are at a church training a group of adults with intellectual disabilities who are preparing for a performance in a few weeks' time.

Photo by Andrew Koay

Photo by Andrew Koay

On another given day, Wang might be conducting a secondary school programme with up to 800 students, or holding a drumming session with elderly participants at an aged care centre.

That’s the beauty and power of taiko drumming, he tells Mothership.

“Drums is the easiest art form, compared to guitar, piano. It is the simplest music instrument that anybody can learn and play. You don’t need to have musical knowledge, you don’t need to know the chords. As long as you have hands, you know how to hit something, you can play the drums.

Drumming is very easy, so people are naturally encouraged to learn. And once — especially for people with low self-confidence — once you manage to get something, you feel good about yourself, that’s how you carry on.”

A Normal (Technical) student with "no dreams at all"

Wang’s belief in taiko as an effective tool to capture the imagination of people who might often otherwise be disengaged from life comes from personal experience.

As a secondary school student at Hai Sing Catholic School, he was placed in the Normal (Technical) stream and was considered to be a youth-at-risk.

“I don’t know what I’m doing back then even if you ask me now. I just let day past by past, you know, go to school. What people do, you just do.

No dreams at all if you ask me, no goals at all in life. You just know that at the end of secondary school life you’ll go to ITE, and then probably [after] ITE you’ll just finish your national service and then you’ll go out and work.”

Wang describes himself as not being academically inclined, struggling particularly with English and communicating with others.

As a result, he tells me he was low in self-esteem and confidence — “I was very quiet and didn’t talk much with people.”

For Wang, the consequence of lacking confidence and his unwillingness to speak up was a loss of opportunity. He was often overlooked in favour of brighter and more vocal students when it came to activities and enrichment programmes.

Started taiko drumming not because he wanted to, but just because enrolment to it was low

It wasn’t until he was in his second year of secondary school that things started to change.

Wang and his friends had been participating in a programme for youth-at-risk run by a Catholic-funded youth centre associated with his school.

Here, they went for weekly sessions that taught them life skills like anger management and the building of self-confidence.

One of the activities the centre ran was a music programme, which included taiko drum classes.

And even though taiko drumming is pretty much at the centre of Wang's life and career now, how he got into it was a confluence of circumstances he simply decided to go along with.

“Initially, to be honest, there was a guitar programme and a drumming programme. And as boys you will usually go for the guitar programme. Learning about guitar, then you can chase girls and so on.

So I signed up for guitar with a few of my friends. But the sign up rate for taiko drums was very low, so the youth worker came and talked to us and encouraged us to join. A group of my friends went [for taiko], so I went with them. I was just following.”

In a twist of pure serendipity, that casual decision to go with his friends over to the taiko drum programme would mark one of the most significant moments to alter the course of Wang’s life.

“When you learn, you fall in love with the action of drumming, with the energy of drumming. And drumming together with a group of people just makes you feel so good.”

Wang had found something he was passionate about, a rarity for him at that time of his life.

Eventually, the members of the taiko drumming programme were asked to put on a performance at the school’s co-curricular activities showcase.

“I think everyone was watching, so I was very very nervous. But the feeling after the performance was great. The first thing that came to mind was ‘wow I can do something like this’. Finally I have a chance to do something like this in front of everybody in the school. I wasn’t just what people had labelled us — an NT student.”

That first drumming performance proved a watershed moment of sorts for Wang. From there, his confidence grew, in tandem with his love for the art of taiko drumming.

Starting a taiko drumming club at ITE

So much so that by the time he enrolled in ITE in 2007, he had the self-assurance to approach school officials and ask for the funds to start a taiko drumming club — a far cry from the boy who was too shy to speak up in class.

“I can’t remember why I had the guts to do so, but I just went to the director of student affairs and said I wanted to start a CCA group. And they took me seriously.

They gave me permission to set up a group and then they gave me, I think, about S$4,000 to buy the instruments and let me run [the club] by myself”.

The group started small — “we started with about five to six [members],” recalls Wang, before it grew to a peak of 30 students.

As Wang's taiko drumming group started to gain more exposure through its performances at school events, people started to approach Wang, offering to pay them to perform at their commercial events.

“Then I realised through what I love, my passion, you can actually earn money as well.”

Moving into teaching

12 years on, it’s clear that Wang’s love for the art form hasn’t dwindled one bit.

He might only be teaching a simple drumming pattern to this group of people with disabilities, but he seems captured by the rhythm nonetheless.

Photo by Andrew Koay

Photo by Andrew Koay

Pacing back and forth between the participants, Wang counts the beats passionately, air-drumming along. His head is nodding up and down in sync with the beats, while his face is squeezed with concentration.

It was this same passion for taiko drumming that drove him to evolve from a performer to a teacher.

“If you are a musician, you learn about the instrument, and after that the second stage is performing. But what is next after performing? Of course you can earn a lot of money doing performances, but the learning stops there.

Then I discovered that teaching is another way of learning. Somehow the process [of teaching] helps you to sharpen and deepen your understanding about certain things.”

Starting with youth-at-risk

So having graduated from ITE, and now being a polytechnic student, Wang knew exactly where he wanted to start if he was going to teach taiko drumming.

Wang had experienced how taiko drums could have a significant impact on a young person’s life and he felt called to give youths-at-risk that same opportunity.

“Back then, I’m not sure now, but back then, the Normal (Tech) students really don’t have opportunities to do [interesting and engaging activities]. Just to give you an example, you after exams we would have those outings? The Express (stream) students will always go for the fun activities, like they’ll visit the food factories, or they’ll go to Sentosa or whatever.

The NT students are usually going to Pasir Ris Park to pick rubbish or do community service because the teachers find it very hard to control us and therefore they are afraid to bring us out.

I cannot blame the teachers either, because my friends were really not easy to control back then.”

For Wang, these behavioural issues often stem from the idea that being an NT student means your options are limited and you can’t do anything significant with your life.

Photo courtesy of Wang Junyong.

Photo courtesy of Wang Junyong.

The solution to this? Confidence.

“I work with a lot of rowdy students, some might call them gangster students. But when it comes to [taiko drum] performances, they don’t dare to do it. The teachers tell me that when they are in school they are very rude, they scold the teachers, they fight in class. But when you ask them to go up the stage to perform, they don’t dare to do it.

Now, this is what we’re talking about — low self-esteem. And I find that, from my own personal experience, if you have confidence, you can achieve a lot more in life.”

Through taiko drums, Wang saw an opportunity to empower these young disaffected students. He wanted to give them a chance to gain some level of mastery over a musical instrument and showcase their talent in performances — something most of them would never have had the chance to experience before.

Just like his own lived experience, he hoped this would inspire youths-at-risk to take hold of their lives and forge paths for themselves.

Making taiko drums his life business

So he started Mangrove Learning and in 2015, right after he finished national service, he got his first big break — a chance to run his taiko drum programme with the first batch of NT students at Anglo-Chinese School (Barker Road).

Wang recalls feeling nervous before going in for the first class of the programme: “We were worried about whether the youths would enjoy drumming or if they would feel that it is ‘lame’.”

Thankfully, the programme was a success, and before long, other schools were getting Wang to run similar courses for them.

Wang remembers a particular Secondary One student who had “serious anger management problems” at a school he was teaching at three years ago.

“He fights in school, he punches the teachers. He’s big-sized, so he does a lot of bullying. Initially when we started, the school actually wanted to remove him from the programme, because [they thought the] drumsticks can be a weapon’. And if this student decided to do some bad things with the drumsticks, like hit someone or start a fight, it will cause big trouble.

But we talked to the school and said give us some time to work with this student.”

After 10 weeks in the programme, the student performed with his peers in front of the whole school to the surprise of his teachers and principal.

Wang says he saw the student again at a recent return visit to the school.

“He’s Sec Three or Sec Four now, and the teachers say he’s very calm now, and doing well in school. Not in terms of academics maybe but in terms of his behaviour.”

Nowadays, Wang has expanded his clientele to include kindergarten children, people with disabilities, and even the elderly, who benefit from a tweaked programme designed to incorporate elements of physiotherapy.

Wang conducting a taiko drumming programme for the elderly. (Photo courtesy of Wang Junyong)

Wang conducting a taiko drumming programme for the elderly. (Photo courtesy of Wang Junyong)

Help and challenges

He too is benefiting from another programme, the Philip Yeo Initiative (PYI), a platform for developing individuals identified as part of the next generation of leaders.

Under PYI, Wang is mentored by David Lim, a former director at Wheelock Properties.

“He always challenges my thought processes. You know being a budding entrepreneur and young guy, we always think that our ideas are the best. But when you brainstorm the ideas, or share them with him, he’ll give you a different point of view.”

However, the growth of his social enterprise has not come without its hurdles.

Wang often finds that people can sometimes be unwilling to pay for Mangrove Learning’s programme, asking him to instead run classes out of goodwill.

It’s an age-old problem for social enterprises, who need to balance the "do-good" nature of their work with the business side of things.

Another challenge is finding more people willing to carry Wang’s vision and run with it.

As it is, Wang is the only full-timer at his company. Two other part-timers help him.

“I have trainers come and go, I have volunteers come and go,” he says, before mentioning that he is on the lookout for people with some sense of rhythm, an interest in learning taiko drumming, and a heart to teach others.

Returning what he gained to society

“I think at the end of the day, what I’m trying to do is to make a difference in my small way, using my own experience — what I’ve benefited from in the youth centre. Now I hope that I can return back to society.”

Back in the church, as the lesson begins to draw to a close, Wang and his volunteer get the group to rehearse everything they’ve learnt so far.

The first few times, there’s stuttering and stumbling — some of the drummers have forgotten certain lines of the pattern, when to join in, or which part of the drum they needed to hit.

But with a couple more attempts they’ve done it, a near-perfect run through.

It may have only been a rehearsal, but the beaming faces across the room don’t seem to care.

For a group of individuals living with intellectual disabilities — some well into their middle-age — they’ve no doubt been written off countless times throughout their lives.

Today, however — with the help of Wang, a volunteer, and a bunch of taiko drums — they’ve achieved something.

If you would like to learn more, engage, support or get involved with Mangrove Learning, you can find out more at their website.

Top image by Andrew Koay

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.