Son of Singapore by Tan Kok Seng is an autobiography covering the early years of a Singaporean's life in our country's early years.

Set against Singapore’s push towards self-governance, it tells the story of a Teochew farm boy who becomes a coolie at the Orchard Road market. He also befriends a group of Chinese dialect-speaking Caucasians who subsequently inspire him to improve himself beyond his humble roots.

Son of Singapore is published by Epigram books, and you can get a copy of it here.

Here, we reproduce a few excerpts from the book:

***

By Tan Kok Seng

Working as a coolie

In my first two weeks I began to be familiar with Singapore street names. At the end of the second week, I had to go to a house in Goodwood Park to collect the usual order form. In that house, the amah was Cantonese.

Each day, it was she who gave me the order, and she usually had it ready, written by her employer’s wife. Today, however, the amah wanted something in addition, but because she was speaking (or so I thought) in Cantonese, I couldn’t understand her properly. All I could hear was, “Yat ko towkay.” (One whole boss.)

This didn’t make sense, but evidently she wanted to see my boss. So I cycled quickly back to the stall.

“Towkay! Towkay!” I cried. “That house in Goodwood Park with the very big and dangerous dog. The amah’s calling for you to go there. She says she wants one whole boss.”

The towkay, fearing something was wrong and that he might lose a customer, went off to the place at once. There, having mustered his courage to face the dog (it was a ferocious Alsatian), he asked the amah what she wanted.

“My coolie told me you wanted me,” he said.

The amah looked mystified. “No, I didn’t ask for you,” she replied. “I only asked your coolie to add to the order 10 cents’ worth of bean sprouts. Your coolie said, ‘All right’, and I thought he would bring them. I didn’t want you to come.”

Bean sprouts in Hokkien are called tow gay, and though I didn’t realise it she had been trying to speak to me in Hokkien. But not knowing how to say ‘10 cents’ in that dialect, she had said it in Cantonese — yat kok — which sounded to me like yat ko (one whole). But how was I to know that in that short sentence she was using two completely different dialects?

When the boss came back to the market, however, he was seething with rage. He turned on his wife. “That stupid boy of yours!” — this was me — “he’s worse than useless!” And he explained to his wife what the amah really wanted.

“She wants 10 cents of tow gay,” he said angrily, “not 10 cents of towkay!” (10 cents of the boss! It was getting worse and worse.)

To his increased fury, the fat Madam was convulsed with laughter, and I, standing behind her husband, nearly laughed too, only he suddenly switched round at me.

“You’ve caused me one hell of a lot of work and trouble!” he shouted in a bid to assert his authority. “With one foot I could kick you out. D’you know that?”

But the fat Madam was the deciding factor in such matters, and she said to me, “Next time listen carefully and don’t make mistakes again. Anything you don’t understand, ask the amah to say it again till you’re sure what it is.”

“All right,” I murmured quietly, and went back to brushing carrots. I was glad she had not scolded me this time. And of course it had to happen at that house with the frightful dog.

The end of the month came, and I proudly received my salary of 30 dollars.

Worked 6.5 days a week, for S$30 a month

Sunday afternoon was my only free time each week, and on the Sunday after getting my pay, I went back home, and even more proudly handed my mother 20 dollars.

Because I slept and had my meals in the boss’s house, which was in a side street close to the market, I needed only 10 dollars for myself for pocket money.

I worked six-and-a-half days a week, and the hours were long, 6am to 10 or 11pm each day except Sunday, when I finished around 1:30pm.

In those days, I was young, but even so I found the work very tiring. By the end of each day, I was all out. I would have a wash and go straight to bed, where I slept like a pig till someone shook me awake the next morning.

But I felt it was a happy and lucky time for me, to have such a job as this, to train me to be strong and tough.

I doubt if many boys of 15 today would think in the same way as I did then.

Today, they would think I was being driven like an ox or a horse, worked all day and knowing nothing.

But youngsters in Singapore at that time were not so clever as they are today; their thinking was slower and simpler. Nor did they demand, or expect, so much.

Part of a lion dance troupe

On the first day of the New Year, we students set out early in the morning in two trucks to visit the homes of the monastery’s benefactors.

There were about 60 of us, all dressed similarly in white vests and baggy black trousers of very light material (excellent for dynamic movement) tied at the ankle with puttees.

Eight of us were experts at manipulating the lion in the lion dance, taking it in turns, two at a time, one the head, the other the tail. The rest were drummers and cymbal players, while others held the monastery flags and banners, and engaged in demonstrations of the monastery’s martial arts.

Our first stop was in Katong, at the home of the chairman of the White Flower Oil Company, who was one of the monastery’s staunchest supporters.

There we spent three-quarters of an hour in the huge forecourt of his house, while he and his family watched from the upper balcony.

Performed for Lim Yew Hock

By 11am we reached the private house of the chief minister.

This was a courtesy call, to show respect, but it was also a precaution, to make it clear that we were not anti-government.

Because although Singapore had an overwhelmingly Chinese population, any group activity on the part of the Chinese was liable to arouse the suspicion of the authorities, and this was particularly so in the case of those of us who practised the arts of self-defence.

The chief minister’s residence was similar to a Malay house, modestly built of wood and tiles, with four or five tiled steps mounting to a main room within.

Directly in front of the house we began our usual lion dance. The lion, however, cannot pay his respects, with all the proper obeisances, until the master of the house appears to light the firecrackers.

And the chief minister did not appear.

For a considerable time we kept the dance going, with the beating of drums and cymbals, but our enthusiasm was distinctly waning.

At last, after a long wait, the chief minister came out from the house. He wore a flowered shirt, while his wife was in sarong kebaya, a Malay lady’s dress, typical of the old Baba-Nyonya, Chinese families who adopted a partly Malay lifestyle.

He walked down two of the steps, lit his firecrackers, and threw them.

The drums and cymbals beat more loudly in appreciation; but unfortunately the chief minister did not know how to throw crackers to a lion.

Instead of throwing them on the ground directly in front of the lion, allowing the lion to bow in acknowledgment and respect, he threw them to one side, where they dropped among the lion’s attendants, one of whom at that juncture was myself, setting most of our trousers on fire.

The crackers and the drums making an equal din, the chief minister did not notice what had happened. The lion continued to rear up and bow.

The lion’s attendants, myself included, manfully carried on our proper functions as best we could, each of us having become his own personal fire extinguisher.

The chief minister remained there for three minutes or so, then turned about abruptly like an army general, and withdrew inside.

Actually, this was the supposed leader of us all in Singapore, and we represented the youth of the country.

Yet he did not say more than two words to us before going back into his house. How, we thought to ourselves, could such a man be our leader, or mean anything to our generation of the future?

This, at any rate, was how we felt as we went on our way. Looking back, I realise now that our judgment was too severe. But we were young, and we felt strongly; nor could we foresee how quickly things were going to change.

Bridging Singapore's people with the British government

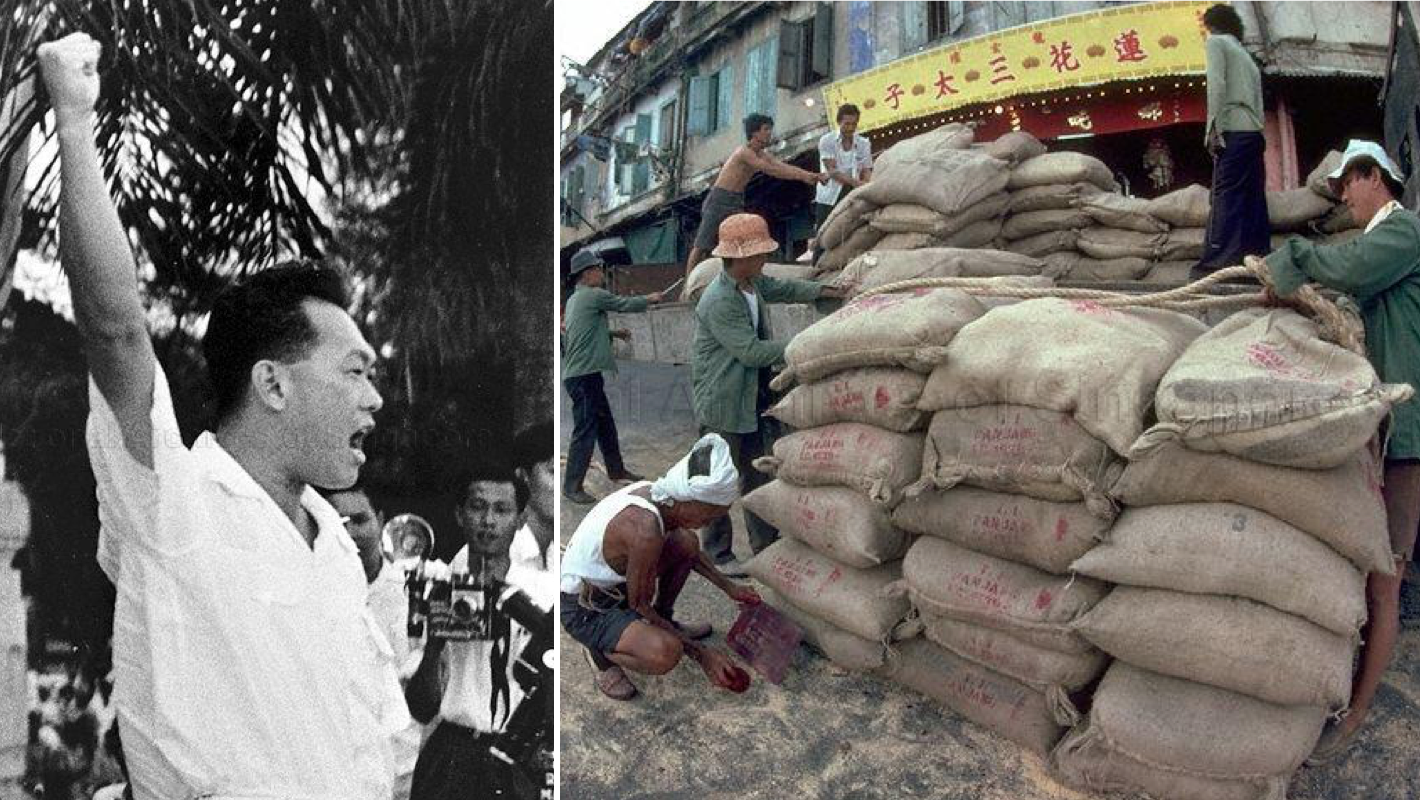

Singapore at that time was advancing towards self-government.

But politically it was still in a twilight phase, in which such men as the chief minister formed a bridge between the old colonial way of government, in which the people had little say in the running of affairs, and the complete self government which was to come.

The curious thing about the British was that though they had the declared aim of self-government, and though they knew Singapore was primarily Chinese, they always hesitated to appoint people who genuinely represented the interests of the Chinese masses.

When in the first general election such people were voted into power with a great majority, the British at first found it most uncomfortable.

Except, of course, for those few who understood Chinese people and their ways, and who were not nervous of what would happen to Singapore under popular rule.

They formed another kind of bridge, a cultural one; and by chance it happened that I came to know some of them, with effects which, though I did not know it at the time, were going to bring great changes in my own life.

What the 1959 General Election was like

Then politics hit us.

A few weeks before Singapore’s first general elections in 1959, I experienced a case of an old joke that came true.

During the time of the political campaigning, all Singaporeans were encouraged to decide what their future government should be. There was a Labour Party, an Independence Party, a People’s Action Party, an Alliance Party, and some others.

In the day, each of them had cars which cruised down Orchard Road past my working place, bearing placards and many young men and girls, keeping up a constant blare of propaganda through microphones.

Each party offered the best of all possible service to the people. But that they were not all talking about quite the same people was suggested by the vehicles used.

The Alliance, then in power, sported huge, expensive limousines; the Labour Party and the People’s Action Party had trucks and vans; the Independence Party had very small cars, such as Ford Prefects and Volkswagens.

Up and down Orchard Road they sailed, making a tremendous din. It was all quite exciting and jolly. At night, in public open spaces, and even on street corners, speeches were given by the party leaders.

One Saturday night, I was returning from the monastery to my sleeping quarters.

Passing the car park opposite Cold Storage, I found a lorry with a number of young people in it seated on benches in the rear, which was uncovered. Two of them I had seen before in the market, though I had never spoken to them.

"If you come with us (to attend a rally), you'll make five dollars."

As I walked past, a man came straight up to me, and said, “Would you like to join these others, and come and listen to the speeches at the party rally?”

I didn’t say anything, and the man added in a lower voice, “If you come with us, you’ll make five dollars.”

Again I said nothing, but glancing up at the faces of my acquaintances in the truck, I saw them both smiling at me in a knowing way. Without making it obvious, they were nodding at me, as if to say, “You can, you know.” So I climbed into the truck, and sat next to them.

“How far are we going?” I asked, half under my breath. “And how are we going to get back?”

“Don’t worry,” one of them whispered in reply. “The whole group picked up here, they’ll bring us back.”

Told to shout "Merdeka!" even though he had no idea what the speeches were about

When we reached the place of the political meeting, which was to be a big, open-air affair, the truck driver told us to sit down on the grass right in front of the speakers’ platform.

Every time the speaker mentioned independence, we were told, we must shout “Merdeka!” (Malay for ‘independence’) three times. We said we would obey these instructions.

But when, long before anything started, I looked round me at such a host of complete strangers in the crowd, I felt scared of shouting. Only when I thought of the five dollars — three days’ salary to me — did I realise I must shout.

During the speeches our cries of “Merdeka!” were at first rather uncertain. But we warmed up to it as we went along and got into the spirit of the thing.

In fact, in the end it was quite fun, though I have no idea what the speeches were about.

When it was all over, and we had all shouted really very well, the driver gave us each five dollars. And I thought to myself, “What a fine thing! Even though I’m too young to vote, I can still do my bit for the nation.”

Leading a country like leading a large family

The results of the election were declared.

People used their own brains in their choice of party. They did not care whether or not they were paid to listen to the candidates’ speeches.

People voted for the party which they really felt was working for them. The result showed clearly which party the people had most trust in.

But often, after a party wins an election and forms a government, within a few months a quarter of those who voted for them are already against them. It shows how difficult it is to be a democratic leader, even in a relatively small country.

In those days I did not understand anything much about politics.

But in my own way of thinking, it seemed to me that leading a country was rather similar to being head of a large family. Some families are peaceful, able to carry on without trouble from day to day, while others are every minute being plunged into trouble.

Comparing uncles

Those families without trouble are those in which the grandfather rules firmly, telling the younger generations what to do.

Even then there are everlasting petty complaints.

The grand children will complain that Elder Uncle is very good, Second Uncle is all right, while Third Uncle is nasty.

Grandfather is able to reply, “Do you have enough food to eat? Do you have clothes to wear, and a comfortable place to sleep? Do you have a good school to go to? If so, what more do you need?”

Where parents cooperate with the head of the family, grandchildren’s complaints lessen with the years as they grow to be adults. Such a family is not only peaceful, but can be prosperous.

As a youngster, it seemed to me that a nation was like a large family, to be dealt with in a similar way.

Top photo composite image, photos via NAS.

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.