We had a problem.

The video challenge we had in mind for Azariah Tan, a Singaporean almost-deaf pianist, was a no-go. We thought it would be fun getting him to listen to several pieces of hardcore metal songs and replicate them on his piano.

But reality panned out differently. The challenge couldn't be done because the many layers in a metal song could not be broken down, interpreted and transmitted by his hearing aid. It would just sound to him like a huge mess of indiscernible noise.

As we stood there in his living room, trying to come up with another idea, he chimed in and said, "Hey, why don't I take off my hearing aid and you guys talk to me. It's really funny when I try to read your lips and fail."

Tan's earnest candour and self-deprecating humour took me by surprise.

Lost 85 per cent of hearing, but has a doctorate in music

Looking at him, it's hard to believe that this young man has only 15 per cent of his hearing left.

Tan suffers from bilateral sensorineural hearing loss, caused by a degenerative condition which destroys the tiny hairs in his ears. He is likely to go completely deaf one day — and it isn't even clear to him when that will happen.

Despite that, Tan is as bubbly as the next guy (at times more so), willing to roll with the punches, and is an accomplished pianist to boot — at the age of 26, he has a doctorate of Musical Arts in piano performance (so that's Dr Azariah Tan to you).

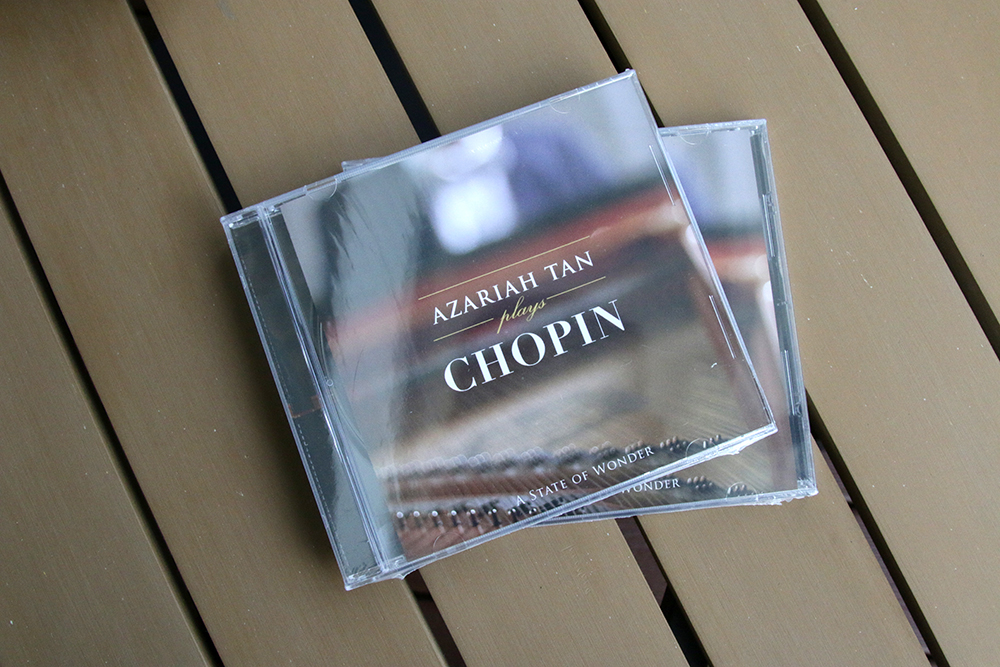

More recently, he released his first album in July: a compilation of recordings he did of pieces by Chopin — a first for a Singaporean — and reception of it in the classical music community has been so positive that he was dubbed "one of Singapore's finest musicians".

Tan recently released an album of Chopin tunes. Photo by Joshua Lee.

Tan recently released an album of Chopin tunes. Photo by Joshua Lee.

How his parents discovered his condition

The only indication of anything out of the ordinary are his barely-noticeable hearing aids — in some way a reflection of how his parents realised their son wasn't just ignoring them.

"My parents suspected that I had [a hearing condition] when I was three. They would call my name and I wouldn't respond. But then they would say other words, like 'Batman' and I would respond."

Tan's parents initially thought he was selectively responding to certain words, but the reality was, regrettably, far more concerning.

They noticed that he was having more trouble hearing and making out words with higher frequencies (like his name "Azariah", which is pronounced "az-uh-RYE-uh") compared to words with lower frequencies (e.g. 'Batman"). His condition was officially diagnosed when he was four.

Perhaps it was a blessing that he was diagnosed as early as he was because Tan says he has absolutely no recollection of transitioning into wearing a hearing aid — or, more specifically, the social awkwardness he might have experienced having to do so.

"I was too young to know, or feel anything. I also don't remember wearing my first hearing aid!"

It was only in kindergarten that the realities of wearing a hearing aid hit him, but not in the way we expected.

"You need to take it out so that the sweat doesn't get into the hearing aid and damage it, which happened a lot!"

That "a lot" refers to, fascinatingly enough, the many times Tan played sports competitively in primary school. At Henry Park Primary, he was part of the school teams in badminton and table tennis, and also also dabbled in swimming and basketball.

He was taken out of Singapore's education system to be home-schooled before he could sit for his PSLE, though.

Tan tells us the period of home-schooling he experienced gave him more flexibility and time to focus on his favourite subjects like math and science, and of course, his music.

Studying music

Getting into a conservatory was not part of Tan's plan actually. His four years of home-schooling were actually meant to prepare him for his 'O' Levels.

"I think my progression in music was much faster during my home-schooling period. I got into music more and more, and I think I did ok with it, so I started looking into options for studying music."

Out of all the schools and professors that Tan's parents approached, Thomas Hecht, who heads Piano Studies at Yong Siew Toh Conservatory, was one of the few who responded positively.

"[Hecht] was very supportive. It made sense too — that when I still had my hearing, to make use of it, to enjoy as much music as I could."

Tan received private tutelage from Hecht until he entered Yong Siew Toh.

Photo by Joshua Lee.

Photo by Joshua Lee.

From there, he went on to the University of Michigan to complete two Master's degrees for music in Piano Performance and Chamber Music, and subsequently, a doctorate of Musical Arts in Piano Performance from the Racham Graduate School.

(And by the way, in case you were wondering about National Service, Tan says he went for his medical checks, and was given a PES F because of his deafness, and that was that.)

And while this seems easy being rattled off in a sentence, the journey there was far from that.

The problem with hearing aids

Now, most of us would know that studying music is not necessarily easier than other disciplines. Studying music as a deaf person, however, is a whole new level of difficult.

And going through a classical musical education, Tan explains, was for him like navigating a minefield.

Tan gives an example of studio classes at the University of Michigan.

In a studio class, students would gather in a concert hall where they would play for and critique one other. For Tan, these classes were particularly challenging.

You see, a concert hall's acoustics is designed for music, not speech. It produces a lot of echoes, and for a person with a hearing aid, hearing people talk in a concert hall can be very difficult.

For Tan himself, it's impossible for him make out speech coherently from where the audience sits in a concert hall.

Tan's hearing aids are hardly noticeable. Photo by Joshua Lee.

Tan's hearing aids are hardly noticeable. Photo by Joshua Lee.

Also, hearing aids have to be toggled to adjust for either speech or music. Tan does this by pressing a button on his hearing aids, but they take a few seconds to switch, so he often ends up missing the first half of a spoken sentence or the first few notes in a sequence of music.

"Also, anything that doesn't follow the wavelength of speech is considered noise, so the hearing aid will cut it out. So in a studio class, there's playing, and then there's speech, followed by playing and then speech."

You can imagine the constant toggling that Tan does just to get through a class.

Here's a sampling of a live performance of his while he was pursuing his doctorate:

&t=1805s

Fortunately, Tan's teacher at the University of Michigan was sympathetic to his needs. He moved the class to sit around the piano on the stage, making it easier for Tan (and the rest) to hear whatever he said.

He adds, with a smile:

"Whenever we make accommodations for people with special needs, it usually benefits everyone."

Tan also faces difficulties when he plays alongside other instruments, like the double bass, for instance:

"The violin is generally at a register that is higher than the piano, so it's distinct, it's separate. Now, if it's a double bass, it's really, really difficult (to differentiate), because it is very low, around the piano's range. The sounds just get blended together and I can't tell which is double bass, which is me. It's like fruit juice! 10 fruits all thrown in together!"

For the most part, Tan is able to get around these challenges, by either playing softly or by looking at what the other party is playing. However, it requires significantly more time and effort on his part to master a piece — to get used to it and understand its challenges.

Unpredictable hearing loss

Tan tells us that these challenges will only get tougher as his hearing worsens. Right now, he only has about 15 per cent of his hearing left — an amount he tracks through regular hearing tests.

"I'm supposed to do one every year but the last one I did was, I think two years ago," he admits sheepishly.

That was done in Michigan using software that isn't available yet in Singapore. It helps to customise one's hearing aids to the needs of the user, Tan says.

And does the prospect of going completely deaf frighten him?

There was a slight hesitance before he replied with a resolute "No".

"I'm not too worried about it. I would say (my hearing level) is not going down super fast. It goes down gradually. But no one can say. It might plunge down suddenly, who knows?"

Because of his impairment, Tan has to put in considerably more effort to master a piece. Photo by Jeanette Tan.

Because of his impairment, Tan has to put in considerably more effort to master a piece. Photo by Jeanette Tan.

If and when his hearing goes, Tan says there is the option of having cochlear implants, which presents its own set of challenges, musically. For one, there's hardly any known classical musician playing professionally with cochlear implants.

But doesn't this unpredictability scare him?

"It's normal to be anxious, but I'm just trying to work with what I have right now."

Now that he has completed his doctorate programme, Tan devotes himself to academia and teaching private students. He shares that teaching is particularly enjoyable for him.

"It's not just playing 'do, re, mi, fa, so' - that's not that fun, really. What's most exciting is teaching them the story behind the music, appreciating the music, making drama out of music, and just having fun."

Aside from that, Tan also performs regularly in recitals, most recently even appearing in a music video with local singer Tay Kewei:

As we concluded our conversation, I recall something he said about not getting too wrapped up in the unpredictable:

"Don't be too concerned with what-ifs. It might come or it may not come so suddenly, but I do what I can now, so that when it comes... (he pauses) I'll be okay."

Looking at this man who "did okay" as a classical pianist against all odds, I have no doubt he'll be fine.

Azariah's first CD album was launched earlier this year. Photo by Joshua Lee.

Azariah's first CD album was launched earlier this year. Photo by Joshua Lee.

If you would like to purchase Tan's album, A State of Wonder, you can do so here.

Top image by Joshua Lee.

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.