Ronald Cheong is an unassuming old man who spends a good part of most of his days at the void deck of his Sengkang block.

The 83-year-old sits there for a few hours a day, quietly repairing shuttlecocks while the rest of the world goes by.

"You see, like this one," Cheong says, holding up a shuttlecock (commonly referred to as shuttles) that was missing a feather. "I'm going to put one feather in here."

Using a pair of pliers, Cheong carefully plucks out a feather from a nearly bald shuttle before inserting it into the first one and applying a tiny sliver of glue. "If it is loose, you put some glue on it, and put it out under the sun to dry."

Image by Ilene Fong.

Image by Ilene Fong.

It's a simple process, but the grin that lights up his face shows the satisfaction he gains from it.

He popped the finished product into his canister of pretty-much-good-as-new shuttles.

As he proceeded to the next one, we began our chat.

Shuttle-talk

Cheong strikes me as a particularly opinionated person, someone who is unencumbered by today's tendency to speak in circles of political correctness.

Take his grouse about foreign players:

"When we take these foreigners in to play for us, they get their citizenship, they get everything, they are well paid. But after five years they say, 'I've got this, I've got that' and they go back. They are here... just to make money."

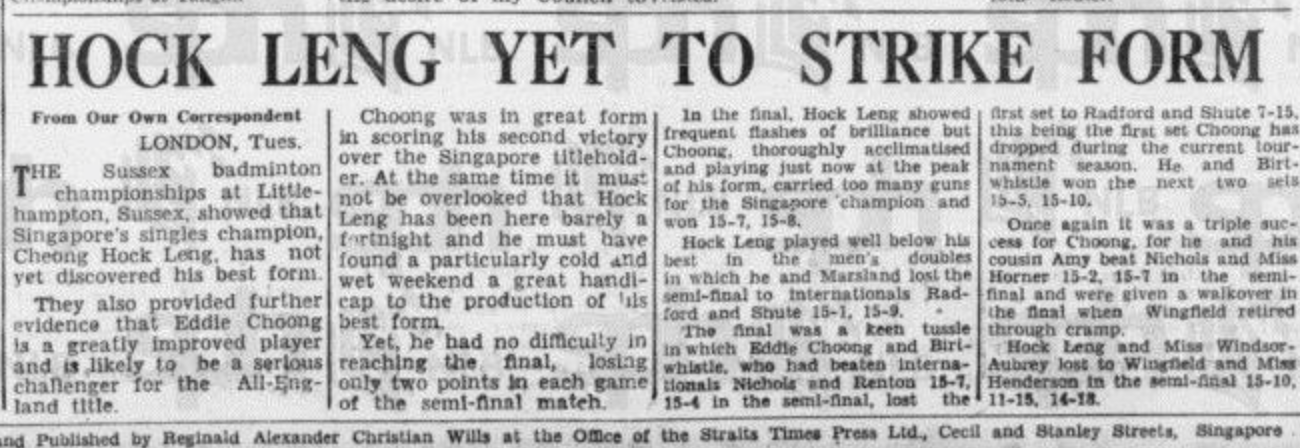

"We don't have [a national player] the likes of the legendary Wong Peng Soon," he adds, pausing ever so slightly after the word "legendary".

"He played the game well. He wasn't that fast, but his playing style emphasised accuracy and judgement."

[related_story]

If like me, Wong's name doesn't ring a bell for you, here he is, a Singaporean, and a four-time winner of the All-England singles title and who Infopedia dubs "one of the greatest badminton players of all time":

Wong Peng Soon. Via.

Wong Peng Soon. Via.

Cheong is convinced that today's players value speed over accuracy, a far cry from the likes of past players like Wong.

"Nowadays you see these people play, they're faster, harder hitters, but there's no judgement or accuracy. They just swing their rackets around; their strokes are not accurate! They hit the shuttle to pass the net, but they don't have any strategy nor foresee what the opponent will send over."

A different breed of sportsmen

Sportsmen of the past were indeed a different breed. For one, playing for the national team used to be a purely voluntary job — unpaid, of course.

Cheong mentioned that his cousin, the late Ronnie Oon, was a teacher who was extremely passionate about badminton and ended up becoming a national badminton doubles champion.

You might remember Singapore's Queen of Sprint, Mary Klass, who had to complete her household chores before she could head out to train.

Sans financial support, and at times also without coaching, all these athletes had were their talent, their gung-ho spirit and, more often than not, a love for the game.

Tang Pui Wah, Singapore's first Olympian, loved the "sense of bliss" that hurdling gave her. Cheong himself loves the satisfaction of hitting a shuttle and hearing the familiar "twack".

Image by Ilene Fong.

Image by Ilene Fong.

Life however, cannot be sustained by passion alone, acknowledges Cheong.

"You can't earn money by playing badminton, you got to survive! So you take the game as a leisurely sport, and you won't go and pursue further."

This, he reasons, is why we haven't seen a badminton champion in such a long time.

Started repairing shuttles as a coach

"40-over years ago!"

That was Cheong's reply when I asked when he started repairing shuttlecocks.

Learning to do this was necessary in his years as a badminton coach, because he needed a large amount of shuttles (as they're known for short) for practice.

It didn't make sense for him to keep buying new ones, especially not when many used ones just needed a little touching up to return to good-as-new condition.

"Singaporean players could always buy new ones. Even the new ones now that cost S$40 and more — Singaporeans won't blink an eye."

Image by Ilene Fong.

Image by Ilene Fong.

It wasn't just the exorbitant cost of shuttles that bothered Cheong, though.

"You see, when you play, you hit the shuttle at the base. But nowadays players like to slam the shuttle from the top; they hit the feathers... the coaches today aren't teaching the players the proper way of hitting!"

It goes without saying that hitting shuttles like that disintegrates them faster.

Image by Ilene Fong.

Image by Ilene Fong.

But even after he stopped coaching, Cheong kept on repairing shuttles.

"Most of it was because of passion for the game. I like the game, and now I want to inspire young ones to play it."

Today, Cheong regularly gives out his finished shuttles to young players at the stadiums and education centres for free, hoping to inspire them into picking up a badminton racket.

And just like that, what started out as a way for him to save money became his lifelong passion project.

Played at his father's badminton court

Cheong's love affair with badminton started when he was around seven years old, thanks to the Eclipse Badminton Party (EBP) — a gathering of about 300 badminton enthusiasts during the pre-WWII days.

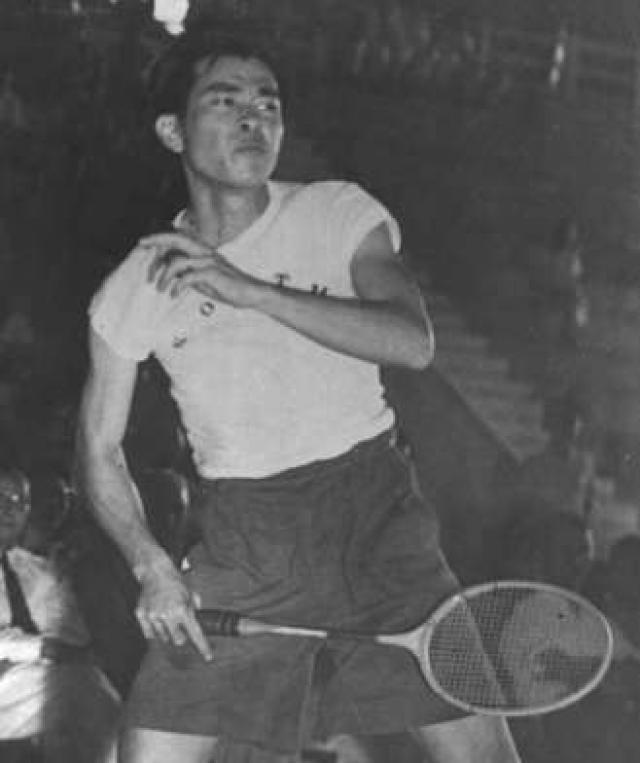

If you were to Google "Eclipse Badminton Party", the first result you would find is this 1939 newspaper clipping:

Via NewspaperSG.

Via NewspaperSG.

Badminton parties were informal playing groups which saw a rise in popularity in the first half of the 1900s. The convenience (you only need two rackets and a shuttle) and simplicity of the game made it particularly mobile and attractive.

"It's a nice game, simple and without hassle. it doesn't need a lot of heavy or hard exercise. Perhaps some light running, some stamina, but it's a simple game."

Cheong's father was the president of the EBP, although funnily enough, he never played. The members of the party voted him in as president simply because his Joo Chiat house had two open-air badminton courts attached to it.

The EBP gathered to play four to five times a week. The days then, Cheong shares, were admittedly much slower, and for these badminton enthusiasts, centred on the beautiful game.

Wong — yes, that legendary Wong — was a regular feature at the badminton games (he represented the Mayflower Badminton Party).

It was he who suggested to Cheong's dad to light up the courts so players could play both during the day and at night.

Smiling like a fanboy, Cheong recalls Wong giving him tips on how to serve properly and strategically.

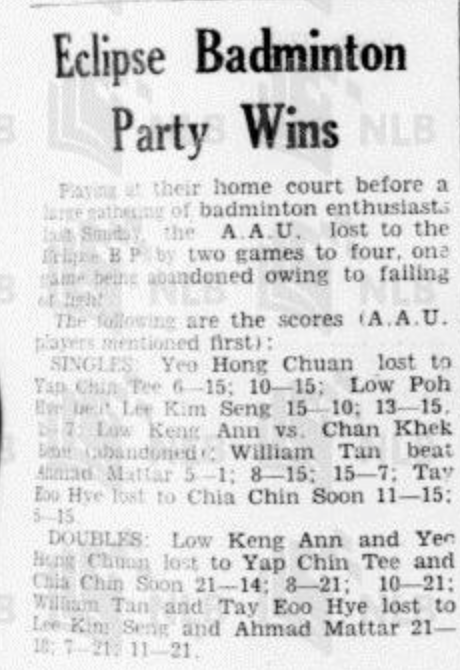

Wong wasn't the only star player who sparred at the Eclipse Badminton Party either — Cheong's cousin Cheong Hock Leng, a former national singles champion, was also a regular.

Here's a newspaper clipping we found of Cheong Hock Leng:

Via NewspaperSG.

Via NewspaperSG.

From benches to coaching

Cheong was on the national reserves team, or the "training squad", as he called it. According to him, he was never called to play although he was relatively skilled, if he should say so himself.

"At that time, the SBA (Singapore Badminton Association) secretary was not so kind to me, lah," Cheong says with a quiet sigh. He would not say more about the matter.

Image by Ilene Fong.

Image by Ilene Fong.

When Cheong recognised that he wasn't going to be fielded in international tournaments, he turned to coaching. He counts as one of his students Fatimah Kumin.

Photo via WaheedaAbdullah.com

Photo via WaheedaAbdullah.com

Fatimah is a local badminton player who turned professional in 1999 at the age of 16. She won a silver medal for Singapore at the 2002 Commonwealth Games, but retired in the same year due to persistent knee injuries.

Chong started coaching Fatimah before she turned professional, although he never really got the credit as her coach:

"I coached her at Bedok Sports Hall. Some Chinese coaches saw her and thought that she had potential. She was already of a certain standard when they put her in tournaments. When she won, the Chinese coaches claimed the glory lah."

Over the years he coached other players at Bedok and Tampines Stadiums — those were classes where he taught them them the basics of the game. He was teaching up to 40 students at once, so there wasn't much time to spot those with good potential.

Even if he wanted to, he says there weren't many players to cultivate:

"Young players are fickle. Today I play badminton, two months later, I'm not playing badminton anymore. You couldn't get one who stayed on long enough."

I asked Cheong what he misses most about playing badminton.

"There's nothing like taking the racket and hitting the shuttle," he says. "Just going for it without a care. The game today is so different."

He still plays occasionally. Cheong notes that today, residents in Sengkang — where he lives — have a badminton court in the estate, but the windy afternoons make it difficult to play a proper game.

"Please write in your article that they want a covered court," he quips cheekily, as he returned to repairing his shuttles — a simple act that reflects his love for the simple, yet beautiful game.

Special thanks to Alvin Oon for arranging the interview. Cover image by Ilene Fong.

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.